An effective weapon for your hum problems: the HumBoy

- By Elvee

- Equipment & Tools

- 80 Replies

Hi there

Hum is one of the most frequent problems encountered by DIYers (and professionals!).

Here is a tool specifically designed to detect, identify, track and locate all types of hum: electrostatic and magnetic coupling, ripple, ground issues, etc.

In principle, the basic equipment of a normal lab or workshop is sufficient to do the job: a signal-tracer or lab-amplifier coupled to an improvised E-mode or H-mode probe for example.

However, a dedicated tool is very useful, especially for difficult cases.

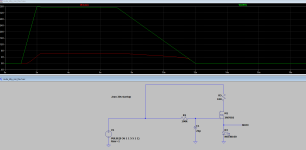

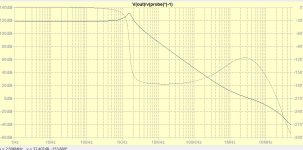

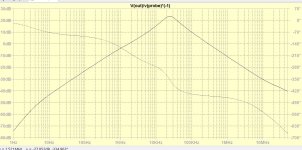

The HumBoy can work as a basic signal-tracer, but it also has special features: one is the very high gain available (insane in fact, literally) and the other is the very high frequency selectivity: it includes three very narrow bandpass filters centered on 50Hz, 100Hz and 150Hz.

The reason for the 50Hz (or 60Hz) is obvious: it is the mains frequency, and basic hum problems are caused by this frequency leaking into circuits through electrostatic or magnetic coupling.

The 100Hz (or 120Hz) has a different origin: it is caused by the rectification process in a supply, and appears in the ripple voltage and the currents around the filter caps and the ground.

The 150Hz is the third harmonic, and is always present to some degree in the mains spectrum because of the waveform distortion, but when a transformer begins to saturate, some of the flux leaks out of the magnetic circuit, and these leaks consist mainly of odd harmonics, primarily third.

When hum appears in an audio chain, it can be a mix of different types, having different origins. You may be able to detect the fundamental by hear, but the ability to discriminate and track each frequency can help in locating quickly the origin(s) of the problem.

Finally, the HumBoy includes a detector coupled to a V-F converter, because the hum frequencies aren't within the optimum sensitivity range of the human ear, and its logarithmic response to the amplitude doesn't help either.

By contrast, the ear is extremely sensitive to small pitch changes, helping to direct the search and quickly locate the source, and hopefully the culprit.

Its input can cope with different types of probes: direct, magnetic or electrostatic.

In the direct mode, it can be connected to a supply voltage, to detect residues of ripple for example.

The magnetic probe (typically a small drum-core choke) sniffs magnetic leaks from magnetic components or AC currents in a wire.

The electrostatic probe (typically a small pigtail left bare at the end of a coaxial cable) identifies unwanted capacitive couplings.

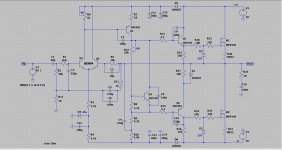

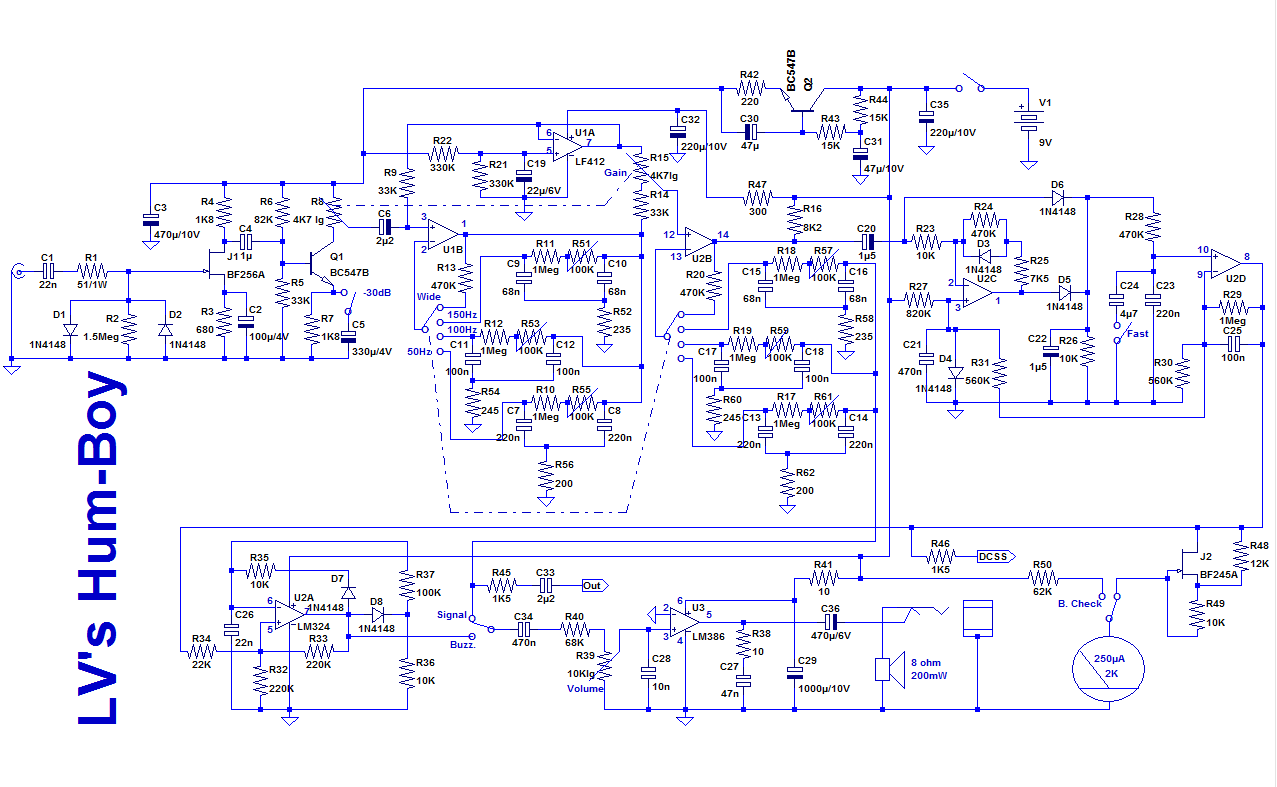

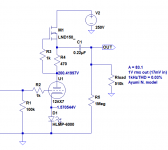

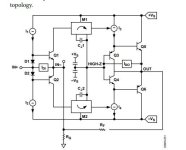

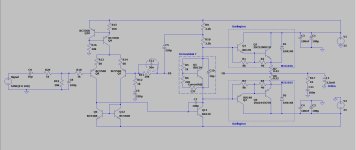

This is the circuit: it is just plain old analogue technology, nothing especially smart or fancy.

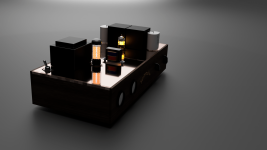

This is the finished tester:

I have included all possible bells and whistles.

These are examples of probes:

The yellow one is the general-purpose magnetic sensor: a 10mH choke, electrostatically shielded.

The black one is the miniature magnetic sensor, capable of locating a single wire in a bundle.

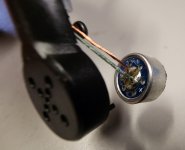

This pic shows its construction: it is made by winding a large number of turns of 0.03mm enameled wire around the center conductor of a miniature coaxial cable.

The inner conductor is made of steel, thus magnetic, and acts as the core of the inductor.

The inductance is 600µH and the resistance 50 ohm.

The last one is the E-type probe, also capable of accurately pinpointing a source.

The sensitivity is absolutely insane: in simple, audio-tracer mode, it is capable of eaves-dropping the audio from a regular telephone pair, without contact just by magnetic induction.

In bandpass mode, it is capable of detecting the 50Hz magnetic field generated by a 110kV HV power line from a distance of ~1 mile.

Hum is one of the most frequent problems encountered by DIYers (and professionals!).

Here is a tool specifically designed to detect, identify, track and locate all types of hum: electrostatic and magnetic coupling, ripple, ground issues, etc.

In principle, the basic equipment of a normal lab or workshop is sufficient to do the job: a signal-tracer or lab-amplifier coupled to an improvised E-mode or H-mode probe for example.

However, a dedicated tool is very useful, especially for difficult cases.

The HumBoy can work as a basic signal-tracer, but it also has special features: one is the very high gain available (insane in fact, literally) and the other is the very high frequency selectivity: it includes three very narrow bandpass filters centered on 50Hz, 100Hz and 150Hz.

The reason for the 50Hz (or 60Hz) is obvious: it is the mains frequency, and basic hum problems are caused by this frequency leaking into circuits through electrostatic or magnetic coupling.

The 100Hz (or 120Hz) has a different origin: it is caused by the rectification process in a supply, and appears in the ripple voltage and the currents around the filter caps and the ground.

The 150Hz is the third harmonic, and is always present to some degree in the mains spectrum because of the waveform distortion, but when a transformer begins to saturate, some of the flux leaks out of the magnetic circuit, and these leaks consist mainly of odd harmonics, primarily third.

When hum appears in an audio chain, it can be a mix of different types, having different origins. You may be able to detect the fundamental by hear, but the ability to discriminate and track each frequency can help in locating quickly the origin(s) of the problem.

Finally, the HumBoy includes a detector coupled to a V-F converter, because the hum frequencies aren't within the optimum sensitivity range of the human ear, and its logarithmic response to the amplitude doesn't help either.

By contrast, the ear is extremely sensitive to small pitch changes, helping to direct the search and quickly locate the source, and hopefully the culprit.

Its input can cope with different types of probes: direct, magnetic or electrostatic.

In the direct mode, it can be connected to a supply voltage, to detect residues of ripple for example.

The magnetic probe (typically a small drum-core choke) sniffs magnetic leaks from magnetic components or AC currents in a wire.

The electrostatic probe (typically a small pigtail left bare at the end of a coaxial cable) identifies unwanted capacitive couplings.

This is the circuit: it is just plain old analogue technology, nothing especially smart or fancy.

This is the finished tester:

I have included all possible bells and whistles.

These are examples of probes:

The yellow one is the general-purpose magnetic sensor: a 10mH choke, electrostatically shielded.

The black one is the miniature magnetic sensor, capable of locating a single wire in a bundle.

This pic shows its construction: it is made by winding a large number of turns of 0.03mm enameled wire around the center conductor of a miniature coaxial cable.

The inner conductor is made of steel, thus magnetic, and acts as the core of the inductor.

The inductance is 600µH and the resistance 50 ohm.

The last one is the E-type probe, also capable of accurately pinpointing a source.

The sensitivity is absolutely insane: in simple, audio-tracer mode, it is capable of eaves-dropping the audio from a regular telephone pair, without contact just by magnetic induction.

In bandpass mode, it is capable of detecting the 50Hz magnetic field generated by a 110kV HV power line from a distance of ~1 mile.

![IMG_1879[1].JPG](/community/data/attachments/1116/1116356-a276955ef730461c1fb27d9539f1855a.jpg?hash=onaVXvcwRh)

/2023/11/26/image/jpeg/DOMPGqzBlzwCAfSrBZIL4p4eZXdl1sqUNiMJDrtP.jpg)