No.So it is really telling us that DBT is useless for checking audio sound quality.

Would you care to evidence that?Esl63, I'm with you on this, applause is very much just a noise, but there's something about the timing and shape of it that we are very sensitive to.

Anyone who thinks high bit rate mp3 is good enough need only make an mp3 of live audience applause and compare to the cd original to hear that they sound nothing alike.

It's noteworthy that this question has been fiercely contested online from the moment the first discussion forums opened. It continues unabated. The question is bedevilled by knotty issues:

1. Every self-identifying 'objectivist' lives with the contradiction of having a clear internal sense of the 'character' of each component in their system. Most spend time and money fettling their audio systems to achieve 'improvements' they can't measure, but enjoy hearing. After all, that's the point.

2. Every self-identifying 'subjectivist' knows that null tests and a long history of failed ABX trials support the conjecture that most things sound the same. Yet that doesn't match their experience – so, like the objectivists, they accept the contradiction and live with it.

3a. Measurement is difficult: you can only measure – within tolerances of mechanical accuracy and proper methodology – one thing, in one way, at one time.

3b. Listening is unlike measurement – it's both cruder and more sophisticated – depending on how you measure such things. Your body is different to a microphone; your brain is different to a digital processor; and your listening environment is unique.

4. 'Impressions' are distorted by bias (ie, foreknowing the cost of a component), but that's a symptom, not a cause: the problem is to perceive our perception. Blind testing for audio makes almost as little sense as blind testing for sight: it's a reporting issue. It takes time and subconscious processing to accurately model external auditory cues, and the process relies on pre-existing frameworks: visual information, experience-based expectation, etc. Blind testing audio is a parlour trick designed to expose the weakness of human perception. It says nothing about audio equipment: the subject of the test is the listener, not the equipment: usually it proves they are merely human.

5. When shade is thrown by objectivists about 'snake oil', it's the same as flat earthers calling out The Grand Conspiracy: it's not relevant. They're angry about something unrelated.

6. Every piece of audio equipment is fundamentally non-identical. That exact combination of parts – numbering in the hundreds – is unique. At some level, however detectable the difference may be, it is not the same as any other 'product'.

7. Consensus. Is widespread agreement around elements of a manufacturer's 'house sound' no more than customers being gulled by branding? Discuss.

8. Science moves on. Improved understanding of auditory perception, and more holistic measurement, will likely harmonise (or at least cast more light on) the present conflict.

Meantime – beyond these generally applicable truths – I vote for the primacy of human experience: if a piece of equipment 'sounds' like something in my system, what happens in my head when I listen to it is what matters. That's why I bought it. Beyond being dumb, however: listening is a faculty that can be trained to a high level of musical discernment. AI – and machines in general – don't care about music: why would I let one dictate a definition of 'excellence' they can't experience? Questions around frequency response are germane: flat seems good to the rational, information-processing part of our brain striving for correctness and low distortion, but you may find it's not how you want to listen – your ear/brain is differently sensitive. Do you tune a system flat it it sounds wrong? Or do you try to adapt to – enjoy? – what looks correct on a graph? Is it a question of taste? Is there such a thing as 'good taste' or 'correct form'? Doubtless discussion will continue . . .

I've had long conversations with knowledgeable engineers and equipment designers and many of them share a sense that sometimes they adopt an approach that works without knowing how it works. Always, too, there's a need to design equipment that measures well, but ultimately is tuned. The idea that machines have an animus, or 'soul' derives from artistic decisions made by those designers. A Ferrari is a Ferrari because of a hundred little decisions that communicate something between the designer and the user. It's not about top speed or braking or G-forces generated, or any of the things that are easily measured. It's the driving experience. Having said that, when they blind-tested Ferrari and BMW drivers to see if they could tell the difference, it also ended badly. Apparently you need to see to drive, otherwise humans just crash – proving that cars are all the same.

1. Every self-identifying 'objectivist' lives with the contradiction of having a clear internal sense of the 'character' of each component in their system. Most spend time and money fettling their audio systems to achieve 'improvements' they can't measure, but enjoy hearing. After all, that's the point.

2. Every self-identifying 'subjectivist' knows that null tests and a long history of failed ABX trials support the conjecture that most things sound the same. Yet that doesn't match their experience – so, like the objectivists, they accept the contradiction and live with it.

3a. Measurement is difficult: you can only measure – within tolerances of mechanical accuracy and proper methodology – one thing, in one way, at one time.

3b. Listening is unlike measurement – it's both cruder and more sophisticated – depending on how you measure such things. Your body is different to a microphone; your brain is different to a digital processor; and your listening environment is unique.

4. 'Impressions' are distorted by bias (ie, foreknowing the cost of a component), but that's a symptom, not a cause: the problem is to perceive our perception. Blind testing for audio makes almost as little sense as blind testing for sight: it's a reporting issue. It takes time and subconscious processing to accurately model external auditory cues, and the process relies on pre-existing frameworks: visual information, experience-based expectation, etc. Blind testing audio is a parlour trick designed to expose the weakness of human perception. It says nothing about audio equipment: the subject of the test is the listener, not the equipment: usually it proves they are merely human.

5. When shade is thrown by objectivists about 'snake oil', it's the same as flat earthers calling out The Grand Conspiracy: it's not relevant. They're angry about something unrelated.

6. Every piece of audio equipment is fundamentally non-identical. That exact combination of parts – numbering in the hundreds – is unique. At some level, however detectable the difference may be, it is not the same as any other 'product'.

7. Consensus. Is widespread agreement around elements of a manufacturer's 'house sound' no more than customers being gulled by branding? Discuss.

8. Science moves on. Improved understanding of auditory perception, and more holistic measurement, will likely harmonise (or at least cast more light on) the present conflict.

Meantime – beyond these generally applicable truths – I vote for the primacy of human experience: if a piece of equipment 'sounds' like something in my system, what happens in my head when I listen to it is what matters. That's why I bought it. Beyond being dumb, however: listening is a faculty that can be trained to a high level of musical discernment. AI – and machines in general – don't care about music: why would I let one dictate a definition of 'excellence' they can't experience? Questions around frequency response are germane: flat seems good to the rational, information-processing part of our brain striving for correctness and low distortion, but you may find it's not how you want to listen – your ear/brain is differently sensitive. Do you tune a system flat it it sounds wrong? Or do you try to adapt to – enjoy? – what looks correct on a graph? Is it a question of taste? Is there such a thing as 'good taste' or 'correct form'? Doubtless discussion will continue . . .

I've had long conversations with knowledgeable engineers and equipment designers and many of them share a sense that sometimes they adopt an approach that works without knowing how it works. Always, too, there's a need to design equipment that measures well, but ultimately is tuned. The idea that machines have an animus, or 'soul' derives from artistic decisions made by those designers. A Ferrari is a Ferrari because of a hundred little decisions that communicate something between the designer and the user. It's not about top speed or braking or G-forces generated, or any of the things that are easily measured. It's the driving experience. Having said that, when they blind-tested Ferrari and BMW drivers to see if they could tell the difference, it also ended badly. Apparently you need to see to drive, otherwise humans just crash – proving that cars are all the same.

Last edited:

Seems you misunderstand what blind testing of audio refers to. The listener is not "blinded" or deprived of visual information but only unaware of which device is being listened to. E.g. in blind A/B test both devices can be shown but listener does not know which device is actually reproducing the audio. Blind testing audio is definitely not a parlour trick but necessary means to mitigate unavoidable perception biases.Blind testing for audio makes almost as little sense as blind testing for sight: it's a reporting issue. It takes time and subconscious processing to accurately model external auditory cues, and the process relies on pre-existing frameworks: visual information, experience-based expectation, etc. Blind testing audio is a parlour trick designed to expose the weakness of human perception. It says nothing about audio equipment: the subject of the test is the listener, not the equipment: usually it proves they are merely human.

Seriously? Please re-read.Seems you misunderstand what blind testing of audio refers to. The listener is not "blinded" or deprived of visual information but only unaware of which device is being listened to. E.g. in blind A/B test both devices can be shown but listener does not know which device is actually reproducing the audio. Blind testing audio is definitely not a parlour trick but necessary means to mitigate unavoidable perception biases.

Blind trials, generally, eliminate expectation bias. Useful. Specifically, medical trials gauge somatic response to drugs by filtering out psychosomatic responses that might respond equally well to a placebo. Medical trials operate on the basis that psychological interference is statistical noise. They seek what is 'actually' happening, not what a patient's brain might perceive is going to happen. Essential, for a drug trial.

Results would be compromised if trials tested only children, or one ethnicity, or those with pre-existing conditions.

Similarly, perception tests - because blind ABX assesment of audio equipment tests the listener, not the product – require a baseline that doesn't alter the perceptive state of the subject. Our auditory system triggers early warning responses: unfamiliar sounds elevate adrenal levels. In the dark, all senses are heightened – on high alert – to compensate for the loss of sight, probing the darkness for remote hazards. Being metaphorically 'in the dark' about what you're listening to certainly eliminates expectation bias, but along with the bathwater goes the baby: the perceptive state changes – shifting to emergency mode, deprived of a framework to hang sense-data on. At the moment you need to patiently marshall rational analysis, the limbic system dominates: "But is this noise an immediate threat?'

Are differences real and large? Real and small? Or all a figment of our branding-sozzled imaginations? Most likely the middle option – depending on your definition of large and small. But what is detectable? What if you can detect a difference, but find it hard to detect or describe that you've detected it? What if you detect the difference but can't detect at all you've detected it? The reporting issue is a problem: words don't translate impulse responses and patterns of brain activity very well. You may as well dance about architecture. All that persists are vague impressions, but that's brains for you: remembering smells better than facts.

To circle back to the relationship between listening and seeing: I strongly suspect that a black speaker painted white would be interpreted (by listeners able to see them) as sounding brighter.

Might take a look at a post from another thread: https://www.diyaudio.com/community/...eaker-cabinets-decoupling.428300/post-8038275

Regarding perceptual testing, there are lots of books and papers on the subject if anyone really wants to keep up with it. More recently Auditory Brainstem Response has been used in some cases to take subjectivity out of the equation.

Regarding perceptual testing, there are lots of books and papers on the subject if anyone really wants to keep up with it. More recently Auditory Brainstem Response has been used in some cases to take subjectivity out of the equation.

Wrong. You really don't know what the blind ABX test is.blind ABX assesment of audio equipment tests the listener, not the product

If listener P constantly and accurately identify products A and B in blind ABX test, then it is accurate test of the product, not the test of the listener. That listener transcendent the "listener test" because of his own impeccable results.

In testing different products C and D in blind CDX test, if the same listener P fails accurately to identify C and D ("flipping the coin"), then it means products C and D have the same sound quality, so again - it is accurate test of the product, not the test of the listener, because that listener P proved his skills before.

If listeners Q fails accurately to identify the same A and B in blind ABX test ("flipping the coin"), then that listener has "cloth ears" and is "sow's ear material", so he should never again participate in blind ABX test (although, his skills may be improved with training). That listener fails both tests - for the listener and for the products.

You really don't know what the blind ABX test is. Please read some basic, introductory texts about blind ABX tests. After that, you should read this: https://www.harman.com/documents/audioscience_0.pdfIn the dark, all senses are heightened – on high alert – to compensate for the loss of sight, probing the darkness for remote hazards. Being metaphorically 'in the dark' about what you're listening to certainly eliminates expectation bias, but along with the bathwater goes the baby: the perceptive state changes – shifting to emergency mode, deprived of a framework to hang sense-data on.

Listeners participating in blind ABX tests are not in the dark - literally or metaphorically. The framework is the same as in any subjective "audiophile" sighted test - your audiophile friend invites you in his room to test two different DAC filter settings ("1" and "2") from his high-end DAC, switching between them while you are listening. You can see everything in his room (including his high-end DAC) and you can see what he is switching ("1" or "2"), so you are not deprived from visual clues. You just don't know what types of filters are "1" and "2" (bias is eliminated), you have to determine if they are sounding the same, or maybe one of them is better than the other.

You really don't know what the blind ABX test is. Your questions above are answered in many science papers, including this short overview: https://www.harman.com/documents/audioscience_0.pdfAre differences real and large? Real and small? Or all a figment of our branding-sozzled imaginations? Most likely the middle option – depending on your definition of large and small. But what is detectable? What if you can detect a difference, but find it hard to detect or describe that you've detected it? What if you detect the difference but can't detect at all you've detected it? The reporting issue is a problem: words don't translate impulse responses and patterns of brain activity very well.

Last edited:

Our brains hold a model of reality, assembled over our lifetime.

Flaws in this model are exploited by magicians, pickpockets, and hi-fi salesmen.

Flaws in this model are exploited by magicians, pickpockets, and hi-fi salesmen.

In that case, you might as well listen to the kitchen radio. Music that makes you feel good, that triggers an emotional response, does that independent from the reproduction quality.From my pov your test isn't so much 'flawed' rather the wrong test. I listen to music for how it makes me feel.

Within reasons of course - you'd probably want to be able to at least understand the lyrics and recognise the melody ;-)

Jan

Yes. And larger boxes deliver more bass. We know all that.To circle back to the relationship between listening and seeing: I strongly suspect that a black speaker painted white would be interpreted (by listeners able to see them) as sounding brighter.

And that is why you need (double) blind testing.

I don't think you grasp the principle yet.

You can see the speakers being tested, but you don't know which one is playing at any one time.

You write down your preferences or ratings or whatever, and only after the whole test run it is revealed which unit was playing the various segments.

So you can only give your judgement based on sound.

The double in double blind refers to the fact that it is also not known by the listener whether the playing unit is changed or not between segments.

Some times the same unit plays consecutive segments.

And that is also the reason why double blind tests are hard on the listener.

Normally there's all kinds of concious and subconsious clues to help you judge, but with DBT you're really back to ears-only.

Hard and stressful. Nobody enjoys it. Especially when you are acutely aware that there's a big chance that you fail, in the sense of scoring 50-50.

Jan

Last edited:

I think so too and I've always wondered who benefits from them or what they are really for.The ABX test only serves for the owner of system and listening room and same records...

Do they perhaps serve to demonstrate that hearing, being a sense, does not provide exactly repeatable results as happens with a machine?

So what?

Even if this were demonstrated, it would not prevent anyone from continuing to perceive differences within their own four walls.

But even if the opposite were demonstrated, that is, that those tests demonstrated that human hearing provides constant and repeatable results, who would benefit from them?

No one.

So my opinion is that in one case or another they prove to be completely useless.

And they do not benefit anyone.

Ah, a three. A "three" is what is always seen in advertisements. Voice actors receive extensive training in how to read them. One method is called the "one, five, three." It refers to reading the list of three items while changing the musical pitch of each item on the list. For example, "exploited by magicians" would be read a musical cord root pitch, the next item at the fifth interval, and the final item at the interval of a third. It sounds like the old NBC commercials where each letter of NBC is read at a different pitch.Our brains hold a model of reality, assembled over our lifetime.

Flaws in this model are exploited by magicians, pickpockets, and hi-fi salesmen.

So, the above quote is an effort at selling us all something. In this case the something is an idea. Humans are always trying to convince other humans of things.

Anyway, the reality is that everything that is sold from breakfast cereal to integrated circuit chips is marketed to humans in order to make money for the seller. You can bet the marketing department at TI has to lot to say about the first page of a datasheet and what bullet points should go there in order get an engineer interested in trying the part. Maybe the IC company can sell millions of dollars worth of product and make way more money some some loser occasionally selling expensive speaker cables (that cost him a lot of money to have custom made).

Regarding the flaws of amateur ABX testing (such as performed by engineers who think its just a simple matter of common sense), here is some information well known by today's professional perceptual scientists:

"A subject's choices can be on merit, i.e. the subject indeed honestly tried to identify whether X seemed closer to A or B. But uninterested or tired subjects might choose randomly without even trying. If not caught, this may dilute the results of other subjects who intently took the test and subject the outcome to Simpson's paradox, resulting in false summary results. Simply looking at the outcome totals of the test (m out of n answers correct) cannot reveal occurrences of this problem.

This problem becomes more acute if the differences are small. The user may get frustrated and simply aim to finish the test by voting randomly. In this regard, forced choice tests such as ABX tend to favor negative outcomes when differences are small if proper protocols are not used to guard against this problem."

Best practices call for both the inclusion of controls and the screening of subjects."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ABX_test

"A subject's choices can be on merit, i.e. the subject indeed honestly tried to identify whether X seemed closer to A or B. But uninterested or tired subjects might choose randomly without even trying. If not caught, this may dilute the results of other subjects who intently took the test and subject the outcome to Simpson's paradox, resulting in false summary results. Simply looking at the outcome totals of the test (m out of n answers correct) cannot reveal occurrences of this problem.

This problem becomes more acute if the differences are small. The user may get frustrated and simply aim to finish the test by voting randomly. In this regard, forced choice tests such as ABX tend to favor negative outcomes when differences are small if proper protocols are not used to guard against this problem."

Best practices call for both the inclusion of controls and the screening of subjects."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ABX_test

Wikipedia is not any kind of a scientific resource. It is the "Free Encyclopedia" and anyone can write anything there. The same applies to this forum and other forums. Anyone anything and unsupported. Just opinions.

From: An Overview of Sensory Characterization Techniques: From Classical Descriptive Analysis to the Emergence of Novel Profiling Methods

There is more on ABX in the professional literature. I can look around for it, but it is known to have a bias towards false negative results in the absence of sufficient user training. BTW, a "false negative" is a type of measurement error when it concludes you can't hear something you actually can hear.

Last edited:

Especially the section "BLIND vs. SIGHTED TESTS – SEEING IS BELIEVING" is very to the point for the current discussion.You really don't know what the blind ABX test is. Your questions above are answered in many science papers, including this short overview: https://www.harman.com/documents/audioscience_0.pdf

But don't think anyone reads it - that would be work, and carry the real danger of shown to be wrong! The horror! Who wants to learn!

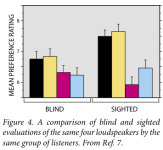

I copy the section of interest. It's just a single page. The figure is attached.

BLIND vs. SIGHTED TESTS – SEEING IS BELIEVING When you know what you are listening to, there is a chance that your opinions might not be completely unbiased. In scientific tests of many kinds, and even in wine tasting, considerable care is taken to ensure the anonymity of the devices or substances being subjectively evaluated. Many people in audio follow the same principle, but others persist in the belief that, in sighted tests, they can ignore such factors as price, size, brand, etc. and arrive at the unbiased truth. In some of the “great debate” issues, like amplifiers, wires, and the like, there are assertions that disguising the product identity prevents listeners from hearing small differences. “Proof” of this is the observation that perceived characteristics that seemed to be obvious when the product identities were known, are either less obvious or non-existent when the products are hidden from view. The truth is not always what we wish it to be. In the category of loudspeakers and rooms, however, there is no doubt that differences exist and are clearly audible. To satisfy ourselves that the additional rigor was necessary, we tested the ability of some of our trusted listeners to maintain objectivity in the face of visible information about the products. The results are very clear. Figure 4 shows that, in subjective ratings of four loudspeakers, the differences in ratings caused by knowledge of the products is as large or larger than those attributable to the differences in sound alone. The two left-hand bars are scores for loudspeakers that were large, expensive and impressive looking, the third bar is the score for a well-designed, small, inexpensive, plastic sub/sat system. The right-hand bar represents a moderately expensive product from a competitor that had been highly rated by respected reviewers. When listeners entered the room for the sighted tests, their positive verbal reactions to the big speakers and the jeers for the tiny sub/sat system foreshadowed dramatic ratings shifts – in opposite directions. The handsome competitor’s system got a higher rating; so much for employee loyalty. Other variables were also tested, and the results indicated that, in the sighted tests, listeners substantially ignored large differences in sound quality attributable to loudspeaker position in the listening room and to program material. In other words, knowledge of the product identity was at least as important a factor in the tests as the principal acoustical factors. Incidentally, many of these listeners were very experienced and, some of them thought, able to ignore the visually-stimulated biases [7]. At this point, it is correct to say that, with adequate experimental controls, we are no longer conducting “listening tests”, we are performing “subjective measurements”.

Bold mine.

Jan

Attachments

- Home

- Source & Line

- Digital Line Level

- DAC blind test: NO audible difference whatsoever