Agreed. It's certainly true that our brain's need to make sense of the limited and in certain ways incorrect information received from the ears (and other senses) makes it easy to accept the illusion without conscious effort.. something which is true in general for all forms of human perception.

I'd take it one step further in the case of listening to music reproduction in that we are psychologically invested and actively want it to work rather than just being passive experiencers. Same with movies. If its good we consciously let go into it to a greater degree and let ourselves be increasingly absorbed into that world, willingly fooled by its false reality. Still, all the while we unconsciously recognize that we are watching a film. Without this ability to willingly go along with the perceptual trick, we'd have to do a lot better job of crafting utterly convincing illusions that were good enough to completely avoid all conscious perception of the experience not actually being reality.

I think of this as the most useful tool we have in the audio tool-chest, which automatically gets applied. We are able to overlook a lot of perceptual noise so that the signal still makes it through.

I'd take it one step further in the case of listening to music reproduction in that we are psychologically invested and actively want it to work rather than just being passive experiencers. Same with movies. If its good we consciously let go into it to a greater degree and let ourselves be increasingly absorbed into that world, willingly fooled by its false reality. Still, all the while we unconsciously recognize that we are watching a film. Without this ability to willingly go along with the perceptual trick, we'd have to do a lot better job of crafting utterly convincing illusions that were good enough to completely avoid all conscious perception of the experience not actually being reality.

I think of this as the most useful tool we have in the audio tool-chest, which automatically gets applied. We are able to overlook a lot of perceptual noise so that the signal still makes it through.

3) It strikes me that such compensation would ideally be made at the mastering (2nd regime) stage rather than upon reproduction. However this assumes the effect is robust enough to work universally across different playback system arrangements, rather than needing to be tuned to a specific playback system.

Thoughts?

Yes I think that the "Dull Center" could be taken care of in the mastering, and it usually is - sort of. Meaning that the phantom center is properly EQed but the side channels remain brighter than the center. They are brighter because they don't suffer the comb filter effects that the phantom center has. Usually this isn't a big problem in music, but can be for dialog.

An EQ that is done mid/side can help of course, but also the phase shuffler works because it simply kills the comb filter notches. It's not without artifacts tho, as some of us have found. Killing the comb filter notches will brighten up the phantom center, which might not be desirable if your EQ is already good. It becomes a balancing act.

Thank you Pano.

Mid/Side EQ is one of the more common mastering tools, applied buy ear by the mastering engineer monitoring via a proper stereo triangle setup, so phantom center timbrel compensation is achieved in that way for traditional commercial music releases. That judgement is subjective of course. It may be that some mastering engineers present a softer phantom center as being correct in a defacto traditional loudspeaker stereo presentation sense, or compensate the other way with a somewhat brighter center phantom. Assuming there is a traditional mastering engineer in the production chain..

For some modern music anything goes, as the barrier to entry has fallen such that some things aren't professionally mastered in the same way as they once were, in which case the mix engineer may be determining that subtle balance.. in some cases with a laptop in a hotel suite using headphones.

I design my microphone arrays and work the subsequent mixing to intentionally achieve a somewhat drier direct/reverberant balance (in terms of sensitivity to direct sound arrival from the source verses reflections and room reverberation) across the center portion of the stereo image, sometimes along with a somewhat different, slightly more present, timbral emphasis. This helps with forward focus and clarity when the recording environment is reverberant, while retaining a good overall reverberant and audience balance which tends to bloom a bit more toward the outside edges of the playback stage.

Interestingly that often slightly emphasizes the upper midrange across the center with the treble range supported somewhat more widely. In other words, after achieving a good overall timbrel balance, I sometimes end up tweaking the EQ of the various microphone channels in the mix so as to use a bit more treble from the wider L/R mic pairs and a bit more upper midrange from the center microphone(s). The overall collective energy balance remains the same, it's more of a subtle trading off on the energy distribution across the playback stage. It's subtle but can be obvious when it all seemingly clicks into place in a very natural sounding way. But what works well for one particular music recording in producing a perceptually natural and correct sounding energy distribution may not translate to that the same combination of recording environment/microphone-arrangement/mixing/mastering-strategy producing a unchanging timbrel response for a person speaking and walking across the performance stage.

It's very much a balancing act as you say, with lots of iterative back and forth, switching of mental listening modes, and coming back later with fresh ears for a sanity check.

Mid/Side EQ is one of the more common mastering tools, applied buy ear by the mastering engineer monitoring via a proper stereo triangle setup, so phantom center timbrel compensation is achieved in that way for traditional commercial music releases. That judgement is subjective of course. It may be that some mastering engineers present a softer phantom center as being correct in a defacto traditional loudspeaker stereo presentation sense, or compensate the other way with a somewhat brighter center phantom. Assuming there is a traditional mastering engineer in the production chain..

For some modern music anything goes, as the barrier to entry has fallen such that some things aren't professionally mastered in the same way as they once were, in which case the mix engineer may be determining that subtle balance.. in some cases with a laptop in a hotel suite using headphones.

I design my microphone arrays and work the subsequent mixing to intentionally achieve a somewhat drier direct/reverberant balance (in terms of sensitivity to direct sound arrival from the source verses reflections and room reverberation) across the center portion of the stereo image, sometimes along with a somewhat different, slightly more present, timbral emphasis. This helps with forward focus and clarity when the recording environment is reverberant, while retaining a good overall reverberant and audience balance which tends to bloom a bit more toward the outside edges of the playback stage.

Interestingly that often slightly emphasizes the upper midrange across the center with the treble range supported somewhat more widely. In other words, after achieving a good overall timbrel balance, I sometimes end up tweaking the EQ of the various microphone channels in the mix so as to use a bit more treble from the wider L/R mic pairs and a bit more upper midrange from the center microphone(s). The overall collective energy balance remains the same, it's more of a subtle trading off on the energy distribution across the playback stage. It's subtle but can be obvious when it all seemingly clicks into place in a very natural sounding way. But what works well for one particular music recording in producing a perceptually natural and correct sounding energy distribution may not translate to that the same combination of recording environment/microphone-arrangement/mixing/mastering-strategy producing a unchanging timbrel response for a person speaking and walking across the performance stage.

It's very much a balancing act as you say, with lots of iterative back and forth, switching of mental listening modes, and coming back later with fresh ears for a sanity check.

Following from that, I'm now convinced that this sort of phantom center correction should ideally be made not in the mastering domain but in the reproduction system domain, as it is a consequence of the stereo triangle speaker reproduction arrangement. Ideally, mix and mastering suites might be setup to correct for this (with an emphasis on minimizing audible artifacts) so that stereo material of all types is mixed and mastered without unconscious compensation for its influence. The resulting stereo output should then be more universally applicable to all playback arrangements.

One more thing I may not be able to unhear anymore lol.

I tried the number counting samples in the beginning of the thread and they did reveal there is a slight but noticable dip in higher freqs in the center part with it, and the corrected version didn't have it though it ended up sounding slightly brighter in center than sides. I will be able to live with this I think lol.

Very interesting stuff, the materials around it I still have to properly process through ~

I tried the number counting samples in the beginning of the thread and they did reveal there is a slight but noticable dip in higher freqs in the center part with it, and the corrected version didn't have it though it ended up sounding slightly brighter in center than sides. I will be able to live with this I think lol.

Very interesting stuff, the materials around it I still have to properly process through ~

Thanks for checking and reporting what you heard.

Not every systems has this effect, many speakers and rooms are so chaotic that they are effectively already shuffled.

Mostly it's an artifact you notice once you get your speakers, and especially your room, dialed in.

@Gutbucket. Mixing and mastering ought to be able to take care of the problem, but IME it isn't done much. You'll have to keep in mind that the vast majority of my recordings are pre 1984. 😛 Of course very few music recordings let you hear the same sound in left, right or center alone so that you can actually judge. And certainly the effect will be a little different for each person and each speaker setup. Tho many head/speaker/ room combos may be close to each other, close enough to do a "one size fits most" EQ.

Not every systems has this effect, many speakers and rooms are so chaotic that they are effectively already shuffled.

Mostly it's an artifact you notice once you get your speakers, and especially your room, dialed in.

@Gutbucket. Mixing and mastering ought to be able to take care of the problem, but IME it isn't done much. You'll have to keep in mind that the vast majority of my recordings are pre 1984. 😛 Of course very few music recordings let you hear the same sound in left, right or center alone so that you can actually judge. And certainly the effect will be a little different for each person and each speaker setup. Tho many head/speaker/ room combos may be close to each other, close enough to do a "one size fits most" EQ.

I take the risk of reiterating some well-know things.

Stereo and the stereo phantom is a matter of intensity and phase (arrival time) between signals of two channels. This goes for the everyday domestic stereo reproduction, and as well as for microphoning:

https://www.dpamicrophones.com/mic-university/stereo-recording-techniques-and-setups

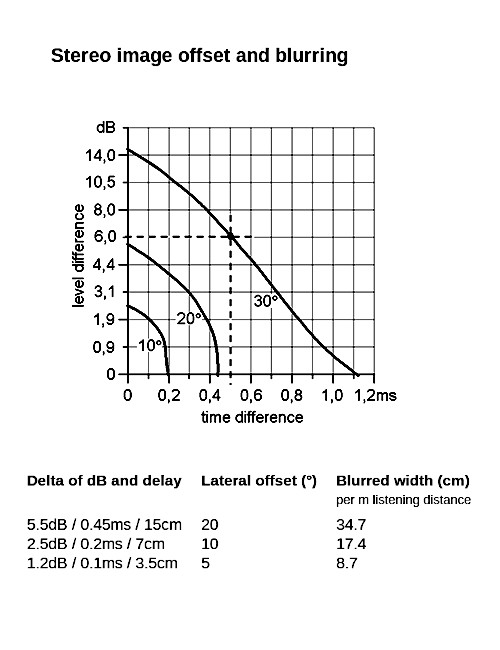

In this paper, a basic graph (..."Fig. 2 Inter-channel differences to provide specific directional information from a two-loudspeaker setup" ...) shows the effects of intensity and phase deltas on the stereo phantom location.

Taking this graph and performing some trigonometry, it gets evident that for a best possible stereo phantom you will have to match both speakers in terms of spl and phase response in a quite tight matter: An interchannel intensity mismatch of only 2.5dB, or a interchannel listening distance delta by 7cm will already cause a subjective shift of the phantom by 10°.

- Case 1: A static delay delta due to asymetrically misplaced speakers will cause a static lateralization of the phantom. This lateralization remains equal for all frequencies. Therefore, in this case, the phantom gets displaced, but itself remains intactly sharp. This phantom displacement is certainly not perfect, but a lesser evil ...

- Case 2: An interchannel SPL frequency response delta instead will will blur the phantom, tearing it apart to both sides, in dependence of the relative channels loudness at different frequencies. This blurring is definitely bad.

- Case 3: An interchannel phase mismatch basically acts as a combination of case 1 and case 2 principles. It's effect on the stereo phantom adds up to the case 1 and case 2 in a specific stereo setup. Further shifting ans blurring the phantom.

In our daily listening room, we well meet a combination of all three cases. Case 1 is easy to remedy by physically shifting your stereo gear around. To cure case 2, you will have to equalize your speakers to match each other best possibly at the sweetspot in terms of SPL response over the frequency range. Personally, I equalize the first wavefront only, and not the room response. To cure case 3, it's more complex. You have to selectively influence on the excess phase of both channels. But it's worth the effort in case of coarser phase mismatches.

As an example for a case 2 assessment: This is a first, uncorrected and thus "native" measurement of my both Quad ESL63 raw (non-)matching after having reworked them. They show an interchannel mismatch (black curve) of 1dB from 1kHz to a 4dB below 10kHz and a max. match error of 7dB above 10kHz:

Looking now at the above graph and the trigonometry: How accurate can the stereo phantom get with such an uncorrected, raw stereo pair, at a typical listening distance of e.g. 2m?

This is why it seems wise to match both speakers best possibly for a distinct listening speetspot. Geometrically, in terms of frequency response, and, if the tools are handy to do so, also in terms of the phase response. Nota bene: By equalizing both speakers independently to a maximal flat frequency response, also the case 2 mismatch inherently gets minimized to a certain extent. But in terms of the stereo phantom precision, not sound coloration correction (correcting for a flat frequency response) primarly matters. It's interchannel match that really is important.

Stereo and the stereo phantom is a matter of intensity and phase (arrival time) between signals of two channels. This goes for the everyday domestic stereo reproduction, and as well as for microphoning:

https://www.dpamicrophones.com/mic-university/stereo-recording-techniques-and-setups

In this paper, a basic graph (..."Fig. 2 Inter-channel differences to provide specific directional information from a two-loudspeaker setup" ...) shows the effects of intensity and phase deltas on the stereo phantom location.

Taking this graph and performing some trigonometry, it gets evident that for a best possible stereo phantom you will have to match both speakers in terms of spl and phase response in a quite tight matter: An interchannel intensity mismatch of only 2.5dB, or a interchannel listening distance delta by 7cm will already cause a subjective shift of the phantom by 10°.

- Case 1: A static delay delta due to asymetrically misplaced speakers will cause a static lateralization of the phantom. This lateralization remains equal for all frequencies. Therefore, in this case, the phantom gets displaced, but itself remains intactly sharp. This phantom displacement is certainly not perfect, but a lesser evil ...

- Case 2: An interchannel SPL frequency response delta instead will will blur the phantom, tearing it apart to both sides, in dependence of the relative channels loudness at different frequencies. This blurring is definitely bad.

- Case 3: An interchannel phase mismatch basically acts as a combination of case 1 and case 2 principles. It's effect on the stereo phantom adds up to the case 1 and case 2 in a specific stereo setup. Further shifting ans blurring the phantom.

In our daily listening room, we well meet a combination of all three cases. Case 1 is easy to remedy by physically shifting your stereo gear around. To cure case 2, you will have to equalize your speakers to match each other best possibly at the sweetspot in terms of SPL response over the frequency range. Personally, I equalize the first wavefront only, and not the room response. To cure case 3, it's more complex. You have to selectively influence on the excess phase of both channels. But it's worth the effort in case of coarser phase mismatches.

As an example for a case 2 assessment: This is a first, uncorrected and thus "native" measurement of my both Quad ESL63 raw (non-)matching after having reworked them. They show an interchannel mismatch (black curve) of 1dB from 1kHz to a 4dB below 10kHz and a max. match error of 7dB above 10kHz:

Looking now at the above graph and the trigonometry: How accurate can the stereo phantom get with such an uncorrected, raw stereo pair, at a typical listening distance of e.g. 2m?

- With a mismatch of approx. 1dB between 1kHz and 4kHz, in this frequency range the phantom would be blurred to a width of 17cm (=2m*8.7cm/m).

- Then, with a mismatch of approx. 2.5dB between 4kHz ... 7.5kHz, the phantom expands to a width of some 35cm.

- Finally, at higher frequencies the phantom gets more and more diffuse, finally getting nebulized to a width of some 70cm and even more.

This is why it seems wise to match both speakers best possibly for a distinct listening speetspot. Geometrically, in terms of frequency response, and, if the tools are handy to do so, also in terms of the phase response. Nota bene: By equalizing both speakers independently to a maximal flat frequency response, also the case 2 mismatch inherently gets minimized to a certain extent. But in terms of the stereo phantom precision, not sound coloration correction (correcting for a flat frequency response) primarly matters. It's interchannel match that really is important.

Last edited:

I just noticed this thread today. I read a few of the posts and then downloaded the paper. One thing occurred to me:

I prefer dipole loudspeakers in relatively reflective rooms. But why? I have always wondered why they sound so much better to me. Perhaps this paper provides some basis for why that is, specifically section 1.4.2 regarding room reflections and comb filtering notches. I have to point out what I think is a flaw in the way these are described. The author says:

With a dipole loduspeaker in a reflective room and the loudspeakers positioned properly away from the front wall, there are plenty of room reflections however the sound is not corrupted by "comb filtering" tonal disturbances. This is because the room reflections are more like the direct sound, and the brain just interprets these as a wider sound source, e.g. the image is widened and enhanced. This is at least how I understand it, at least.

Placing the loudspeaker in a relatively bare room lacking wall treatments sounds like heresy to many. When listening to very directive loudspeakers, many people attempt to remove the room as much as possible to make the speakers sound tonally balanced. This is because the room will not return sound with a tonal balance that is anything like the direct sound due to lack of off-axis radiation above some middle frequency band. These kind of speakers always sound very wrong to me no matter how they are set up. A good dipole loudspeaker is the polar opposite of this, and you want to let the room reflections shine through as much as possible. The space should not be like a cave, but the front wall can be a hard planar surface and the walls plain with no acoustic adsorption or diffusion present. Only the rear wall should be dead, and perhaps a thin carpet over a hardwood floor and a soft sofa to soak up some energy and keep the reverberant time down to a resonable level. It makes for a very enjoyable experience, including the phantom image!

I prefer dipole loudspeakers in relatively reflective rooms. But why? I have always wondered why they sound so much better to me. Perhaps this paper provides some basis for why that is, specifically section 1.4.2 regarding room reflections and comb filtering notches. I have to point out what I think is a flaw in the way these are described. The author says:

Room reflections, except in very small rooms and with speakers too close to walls, occur too late to be perceived as causing comb filtering. This is not how hearing and the ear+brain perception system works, but I see this kind of thing mentioned all the time. "Hearing" is not like a microphone-measured frequency response. Differences between the original source and a very early-arriving secondary one (e.g. from a cabinet edge, etc.) WILL be perceived as comb filtering. But after a few milliseconds the brain is not processing sound in that way, and instead is getting a sense of the "space" where the listener is located. These later arrivals are essentially folded into the brain's perception of what is nearby, and this is not per se like comb filtering of the early sound....room reflections and reverberation from all directions, while creating new cancellations of their own...

With a dipole loduspeaker in a reflective room and the loudspeakers positioned properly away from the front wall, there are plenty of room reflections however the sound is not corrupted by "comb filtering" tonal disturbances. This is because the room reflections are more like the direct sound, and the brain just interprets these as a wider sound source, e.g. the image is widened and enhanced. This is at least how I understand it, at least.

Placing the loudspeaker in a relatively bare room lacking wall treatments sounds like heresy to many. When listening to very directive loudspeakers, many people attempt to remove the room as much as possible to make the speakers sound tonally balanced. This is because the room will not return sound with a tonal balance that is anything like the direct sound due to lack of off-axis radiation above some middle frequency band. These kind of speakers always sound very wrong to me no matter how they are set up. A good dipole loudspeaker is the polar opposite of this, and you want to let the room reflections shine through as much as possible. The space should not be like a cave, but the front wall can be a hard planar surface and the walls plain with no acoustic adsorption or diffusion present. Only the rear wall should be dead, and perhaps a thin carpet over a hardwood floor and a soft sofa to soak up some energy and keep the reverberant time down to a resonable level. It makes for a very enjoyable experience, including the phantom image!

If you want really great stereo middle, place a dummy speaker in the middle - or better, have your buddies do it when you are away.

Putting aside my usual tendency to disparage wannabee-engineer "explanations" of psycho-acoustics... OK, I can't put it aside today. Just want to say there is a time-course for "learning" the sound of music rooms and so there must be some sophisticated analysis your hearing system does before it "understands" the sound system playing there and makes it sound OK. In any case, not just the usual grade-school geometry of post 1027.

B.

Putting aside my usual tendency to disparage wannabee-engineer "explanations" of psycho-acoustics... OK, I can't put it aside today. Just want to say there is a time-course for "learning" the sound of music rooms and so there must be some sophisticated analysis your hearing system does before it "understands" the sound system playing there and makes it sound OK. In any case, not just the usual grade-school geometry of post 1027.

B.

It wasn't until the mid 1980s that I had the opportunity to hear large, high end systems that had been meticulously tuned for left/right symmetry. Only then did I discover what a strong influence that had on the phantom center image - in fact the entire image. Once you get there, things click into place. But of course that strong symmetry would also cause strong comb filtering. I later found this with my systems.

True, but the late reflections are not what is causing the tonal shift due to comb filtering, it's the direct sound that does it. Strong reflections can muddle ans obscure the direct comb filtering, making the effect anywhere from less noticeable to absent. On the system I was using at the beginning of this thread, the indirect sound (room) was 10-12dB below the direct sound across the spectrum. That's not typical, AFAIK.Room reflections, except in very small rooms and with speakers too close to walls, occur too late to be perceived as causing comb filtering.

With a big OB in the same listening room, the tonal hole in the middle was much less obvious.

Well, you do realize that the best listening room I ever had was an actual cave - and I was using open baffle speakers? 😀The space should not be like a cave,

Yes, that works best for me. However I do like some diffusion behind, rather than a perfectly flat wall.Only the rear wall should be dead,

This is why it seems wise to match both speakers best possibly for a distinct listening speetspot. Geometrically, in terms of frequency response, and, if the tools are handy to do so, also in terms of the phase response. Nota bene: By equalizing both speakers independently to a maximal flat frequency response, also the case 2 mismatch inherently gets minimized to a certain extent. But in terms of the stereo phantom precision, not sound coloration correction (correcting for a flat frequency response) primarly matters. It's interchannel match that really is important.

Nice writeup. Thx.

Strongly agree...i think the more identical the speakers are in terms of frequency response and phase, the better the central image.

Likewise, the more symmetric the room response is, and the more equidistant the speakers are, the better the central image.

I think most everyone agrees with those ideas.

And i think the best test of achieved left/right symmetry & equality, is running mono to both sides...if the image isn't rock solid center, without waver with whatever song as frequency content changes, something can be improved imo/ime.

Then, in stereo, when the most prominent central image softens or wanders off center....i just chalk it up to how well the song was "stereo mastered".

Some just plain wander....some seem meant to soften the central image.

To cure case 2, you will have to equalize your speakers to match each other best possibly at the sweetspot in terms of SPL response over the frequency range.

There is a cheap and dirty trick we used to do in live audio. We'd make "stereo" from mono with a 31 band equalizer. On one channel you would alternate each band up, down, up down, etc. for all 31 bands On the other channel - down up down up ect, so that the left and right were mirror images of each band. Quite the comb mess! But it did spread mono into a sort of pseudo stereo. 🙂And i think the best test of achieved left/right symmetry & equality, is running mono to both sides...if the image isn't rock solid center, without waver with whatever song as frequency content changes, something can be improved imo/ime.

Some thoughts about the comb filtering annoyance in a stereo system, along with using some trigonometry.

First, for the grim and obstinate perfectionist man sitting immobile for hours: In a stereo setup, sitting right in the middle of the correct corner in the stereo triangle, each ear gets a lateral offset of 10cm (assuming an inter-ear distance of 20cm). Which translates into comb filtering with a first notch at 1920Hz (for a 300cm speaker basis and a listener distance of 260cm, which makes for an equilateral triangle). So iron discipline does not help. There is comb filtering artefacts even for the brave ones.

The more emotionally listener will not sit still. This type of melomane may slowly shift the head to both sides by 10cm or so, so that one ear gets right to the center of the stereo triangle, while the lateral ear will get a consecutive offset of 20cm. For the central ear, the first notch frequency then will be continously shifted upwards until the ear is right in the center, where the notch disappears beyond the highest reproduced system (and also biologically perceivable) frequency. Even at a lateral offset of 1cm of the ear from the symmetry line there might still be a first notch lurking at the very youngest auditors at 19'200Hz. For the lateral ear instead, the first notch frequency will decrease until it reaches 960Hz at max. head shift of 10cm.

Now, music audition might be a pleasure to share. If you listen to the music with your buddy, you both symetrically and comfortably seated aside the centerline of the triangle and at an inter-buddy distance of 70cm, your both ears will be lateralized by 25cm and by 45cm. This translates to a first notch at 770Hz for the inner ear and at 430Hz for the outer one.

And in extremis, if you get psychoacoustically aroused and have the urge to walk around, wandering to the right angle line of the stereo basis in front of one of the speakers will gratify you with a first notch at around 140Hz.

There is strong evidence from these numeric musings, that shifting your ears around seems a rather helpless attempt to get rid of the comb filtering effect. If you really want to tame this notchy story, you will have to resort to a brute-force approach, setting up a trinaural system instead. It is said that in a trinaural system the center speaker has to be full-featured because it takes the full mono load. This might be somehow true for a standard trinaural system, but not for this application: For a notch-ex approach, you also could high-pass filter the center speakers response. And when introducing interdriver spacings and xovers on the center line, then do that in an educated way. Go below the frequency where the first lobing artefacts would occur, not only below the min. notch frequency you want to eliminate. To avoid any lobing, D/lambda must be max. 0.5. Hence, the xover frequency must be lower than 115Hz for a 300cm stereo base, and lower than 170Hz in the case of a 200cm stereo base. Which is way below any comb filtering artefacts occuring during a more or less regular audition. And therefore, by taking care not to exceed the xover limits on the frontline, you will inherently eliminate any comb filtering artefacts altogether.

A german enthousiast is currently working/experimenting on such a setup:

https://www.aktives-hoeren.de/viewtopic.php?p=222585#p222585

First auditions seem to show most satisfying results in terms of the stereo phantom. So maybe comb filtering by itself, or maybe the steady, dynamic shift of the affected frequencies while moving you head around, might have a negative influence on the stereo phantom.

First, for the grim and obstinate perfectionist man sitting immobile for hours: In a stereo setup, sitting right in the middle of the correct corner in the stereo triangle, each ear gets a lateral offset of 10cm (assuming an inter-ear distance of 20cm). Which translates into comb filtering with a first notch at 1920Hz (for a 300cm speaker basis and a listener distance of 260cm, which makes for an equilateral triangle). So iron discipline does not help. There is comb filtering artefacts even for the brave ones.

The more emotionally listener will not sit still. This type of melomane may slowly shift the head to both sides by 10cm or so, so that one ear gets right to the center of the stereo triangle, while the lateral ear will get a consecutive offset of 20cm. For the central ear, the first notch frequency then will be continously shifted upwards until the ear is right in the center, where the notch disappears beyond the highest reproduced system (and also biologically perceivable) frequency. Even at a lateral offset of 1cm of the ear from the symmetry line there might still be a first notch lurking at the very youngest auditors at 19'200Hz. For the lateral ear instead, the first notch frequency will decrease until it reaches 960Hz at max. head shift of 10cm.

Now, music audition might be a pleasure to share. If you listen to the music with your buddy, you both symetrically and comfortably seated aside the centerline of the triangle and at an inter-buddy distance of 70cm, your both ears will be lateralized by 25cm and by 45cm. This translates to a first notch at 770Hz for the inner ear and at 430Hz for the outer one.

And in extremis, if you get psychoacoustically aroused and have the urge to walk around, wandering to the right angle line of the stereo basis in front of one of the speakers will gratify you with a first notch at around 140Hz.

There is strong evidence from these numeric musings, that shifting your ears around seems a rather helpless attempt to get rid of the comb filtering effect. If you really want to tame this notchy story, you will have to resort to a brute-force approach, setting up a trinaural system instead. It is said that in a trinaural system the center speaker has to be full-featured because it takes the full mono load. This might be somehow true for a standard trinaural system, but not for this application: For a notch-ex approach, you also could high-pass filter the center speakers response. And when introducing interdriver spacings and xovers on the center line, then do that in an educated way. Go below the frequency where the first lobing artefacts would occur, not only below the min. notch frequency you want to eliminate. To avoid any lobing, D/lambda must be max. 0.5. Hence, the xover frequency must be lower than 115Hz for a 300cm stereo base, and lower than 170Hz in the case of a 200cm stereo base. Which is way below any comb filtering artefacts occuring during a more or less regular audition. And therefore, by taking care not to exceed the xover limits on the frontline, you will inherently eliminate any comb filtering artefacts altogether.

A german enthousiast is currently working/experimenting on such a setup:

https://www.aktives-hoeren.de/viewtopic.php?p=222585#p222585

First auditions seem to show most satisfying results in terms of the stereo phantom. So maybe comb filtering by itself, or maybe the steady, dynamic shift of the affected frequencies while moving you head around, might have a negative influence on the stereo phantom.

Last edited:

Good one! haven't heard of that before...There is a cheap and dirty trick we used to do in live audio. We'd make "stereo" from mono with a 31 band equalizer. On one channel you would alternate each band up, down, up down, etc. for all 31 bands On the other channel - down up down up ect, so that the left and right were mirror images of each band. Quite the comb mess! But it did spread mono into a sort of pseudo stereo. 🙂

Hey, sometimes we just have to say, if it sounds good, it is good, huh? 🙂

The trinaural system is very interesting. I have a small SSS (single stereo speaker, matrixed) on my desk with a subwoofer under the desk. I use it mostly to play along songs with my guitar and for background listening while working on a PC. I am still in the search of a perfect mono speaker, but I am afraid, I will have to build three instead of just two in the end🙂

There is a cheap and dirty trick we used to do in live audio. We'd make "stereo" from mono with a 31 band equalizer. On one channel you would alternate each band up, down, up down, etc. for all 31 bands On the other channel - down up down up ect, so that the left and right were mirror images of each band. Quite the comb mess! But it did spread mono into a sort of pseudo stereo.

This is a neat trick, and maybe apt for a recycling:

Some people praise a stereo image to "snap-in" at the perfect listening location (as an aside: there is no perfect location in a stereo system because of the ubiquitous comb filtering). But most of us do not listen secured in a vice. Therefore, in a practical hearing session we steadily move, and this might come along with a whole sequence of snap-in's and snap-out's in such a "perfected" system. Kind of an acoustic Flip-Flop and potentially an annoyance.

Using the trick described by pano, but in a very moderate way, an approach might be found to blur the stereo phantom to smooth this switching behavior a bit. So blur this phantom, but blur it only a little bit, and blur it a contolled bit. Say, blur it by an asymmetry of 1dB, which would broaden a stereo phantom to a width of some 20cm at a 2m listening range. To do so in a well designed stereo system, one might first correct the frequency response to a best possible match between both L and R speakers, but then convolve a symetrically mirrored, narrow-spaced 0.5dB up-and-down filter response onto their response characteristic. This introduced ripple would still allow for a potentially excellent frequency response for each individual speaker.

The decently and controlled blurred phantom resulting then certainly would no more be "perfect" in terms of a razor-sharp stereo sine-wave location. And this is excactly what we want: Because this slight blurring would eventually make transitions from the previously "snapped-in" to the "snapped-out" hearing locations smoother, and thus result in a better long-term tolerance of these transitions while listening.

Last edited:

Yep. I think that's what it takes. I've set up a trinaural system with various presets to compare to stereo.There is strong evidence from these numeric musings, that shifting your ears around seems a rather helpless attempt to get rid of the comb filtering effect. If you really want to tame this notchy story, you will have to resort to a brute-force approach, setting up a trinaural system instead.

I think the major tradeoff in solidifying the center channel (and avoiding combing from left & right) comer is a shrinkage of the size of stereo's apparent sound field.

I've found it's most always a good tradeoff..... clearer sound....and wide as heck sweet spot. Not always though, some stereo recordings are simply excellent.

I spent about half a year trying to use a center speaker that was identical to left and right, from 100Hz up.It is said that in a trinaural system the center speaker has to be full-featured because it takes the full mono load.

Here's a thread about the speakers https://www.diyaudio.com/community/threads/syn-10.383607/

It worked, but i was always seemed to be fighting it some...switching between presets/matrices that sent various amounts of addition/subtraction to left-center-right.

And comparing them to stereo, mono, etc.

On average, I like one LCR preset the best ..a simple version of Gerzon's work.

But often not really knowing what i like best.

Very recently I added a sub to the center speaker, so I now have three of the same speaker stacks.

I'm loving it. It is a big improvement for both the central image and the overall sound field.

I'm using the same favorite LCR preset I liked without the center sub, and it's now my default setup without the urge to hop around presets.

Purely anecdotal evidence. I know.

But it's kinda startling how much changing the center to full range accomplished ...brings home the importance of having a low frequency foundation, for any and all speakers, i guess.

Obviously a trinaural system would fix the phantom center image. But then it wouldn't be a phantom any more, would it?

I have experimented with a band limited center speaker playing a various levels, it can be effective at smoothing out the tonal shift if done correctly. It also makes the center image tighter and more defined. No surprise there.

But for those who choose to use the standard two speaker set-up, there can be problems with the center versus the sides. Mid-Side EQ can be used to good effect, as @wesayso has explained. The phase shuffle is meant to fix the problem in another way, in theory accounting for any movement of the listener's position. It does work for me. There are several ways to fix the phantom center, each works and has its advantages and its limitations.

I have experimented with a band limited center speaker playing a various levels, it can be effective at smoothing out the tonal shift if done correctly. It also makes the center image tighter and more defined. No surprise there.

But for those who choose to use the standard two speaker set-up, there can be problems with the center versus the sides. Mid-Side EQ can be used to good effect, as @wesayso has explained. The phase shuffle is meant to fix the problem in another way, in theory accounting for any movement of the listener's position. It does work for me. There are several ways to fix the phantom center, each works and has its advantages and its limitations.

- Home

- Loudspeakers

- Multi-Way

- Fixing the Stereo Phantom Center