LOL, so the setup was bad. The speaker itself is NOT nasal. What do you define as nasal sounding strings? The sound of pinched harmonics? The EMIM and EMITS are not nasal. Had to be something else it was not the Beta

That's just woofer directivity not baffle step. Baffle step refers to an on-axis increase in SPL not to polar response. The polar response does not go to 360 degrees until well below 200 Hz and even then there is some fall off at the rear just due to shading from the box. And the crossover would be lower than 900 Hz, but that's not important.

LOL, so the setup was bad. The speaker itself is NOT nasal. What do you define as nasal sounding strings? The sound of pinched harmonics? The EMIM and EMITS are not nasal. Had to be something else it was not the Beta

What I heard sounded to me as if there were serious peaks somewhere in the 1-2 kHz region. The string sound was hard and shrill. This wasn't a subtle issue; it drove both Lynn and me from the room in seconds.

I can't be sure of what was wrong (recording, electronics, speakers, room, etc.), because all I could hear was the end result. My point wasn't to guess at the cause; it wasn't my problem to solve. My main concern was that this was a demonstration by the the exhibitor for a TAS reviewer, which would lead me to expect that the system would be shown off at its best. It's scary to imagine that anyone actually thinks that's what orchestral instruments really sound like.

Gary Dahl

I heard the same thing; the sound was grotesque, harsh and shrill, with bass pretty much AWOL. What's weird is that nobody else noticed except the two of us; it was like being in one of those movies where only the protagonist notices what's going on around him. That, in a way, was the most surprising thing of all; nobody noticed how awful it sounded.

Room placement or bad recording? No. This sounded like 1~5 kHz was elevated by 5 to 10 dB, with more than one peak, and distorted as well. Like a college-dorm PA system on Friday night after midterms. At the time, I had no idea what was wrong, and still don't. Rather than make a scene (and get thrown out of yet another room), we both snuck out quietly, puzzled and a little dismayed.

Gary had pretty much the same reaction I did: an amazed expression and "didn't they hear that?" A system that costs more than $100,000, in a room that's $5,000 for two and half days, seen by hundreds of visitors, and something sounds very broken. What, I do not know. Room placement ain't gonna push up the midrange by 5~10 dB and add distortion, and I've never heard a classical recording sound like that, unless it was made on a hidden Norelco Carry-Corder with a $25 Shure vocal microphone.

Other people raved about the sound, so I guess the sound must have been fixed at some point. Bad panel? Amplifiers decided to start oscillating in the RF range (which will thoroughly destroy sound quality)? Corroded connections in the crossover, or a part shaken loose in shipment? Could have been anything, in a show environment. But it definitely wasn't bad room setup, or a mediocre recording.

I set up and ran the demo room for Audionics at the Chicago Summer CES several years running, and know from bitter experience that rooms can sound really bad for the most unexpected and unlikely reasons. Products are frequently damaged in shipment, crossovers disintegrate, and RFI is ever-present.

Gary and I heard two other rooms that even worse, and were some of the worst sound I've ever heard at a hifi show. The exhibitors were blithely unaware of what was screeching out of the speakers; I wondered if they were deaf, in profound denial, or simply didn't know what actual music sounded like. The most charitable interpretation was the latter, but it prompted a lot of questions why the exhibitor spent such a lot of money for such a poor result.

Room placement or bad recording? No. This sounded like 1~5 kHz was elevated by 5 to 10 dB, with more than one peak, and distorted as well. Like a college-dorm PA system on Friday night after midterms. At the time, I had no idea what was wrong, and still don't. Rather than make a scene (and get thrown out of yet another room), we both snuck out quietly, puzzled and a little dismayed.

Gary had pretty much the same reaction I did: an amazed expression and "didn't they hear that?" A system that costs more than $100,000, in a room that's $5,000 for two and half days, seen by hundreds of visitors, and something sounds very broken. What, I do not know. Room placement ain't gonna push up the midrange by 5~10 dB and add distortion, and I've never heard a classical recording sound like that, unless it was made on a hidden Norelco Carry-Corder with a $25 Shure vocal microphone.

Other people raved about the sound, so I guess the sound must have been fixed at some point. Bad panel? Amplifiers decided to start oscillating in the RF range (which will thoroughly destroy sound quality)? Corroded connections in the crossover, or a part shaken loose in shipment? Could have been anything, in a show environment. But it definitely wasn't bad room setup, or a mediocre recording.

I set up and ran the demo room for Audionics at the Chicago Summer CES several years running, and know from bitter experience that rooms can sound really bad for the most unexpected and unlikely reasons. Products are frequently damaged in shipment, crossovers disintegrate, and RFI is ever-present.

Gary and I heard two other rooms that even worse, and were some of the worst sound I've ever heard at a hifi show. The exhibitors were blithely unaware of what was screeching out of the speakers; I wondered if they were deaf, in profound denial, or simply didn't know what actual music sounded like. The most charitable interpretation was the latter, but it prompted a lot of questions why the exhibitor spent such a lot of money for such a poor result.

Last edited:

This might provide a few clues ... Let's talk PS Audio and RMAF 2014 | General discussions and miscellaneous ramblings | Forums | PS Audio

I've done enough shows to know they really aren't all that much fun for the exhibitor. Under ideal circumstances, they are both exciting and bone-deep exhausting, but more often, you're struggling with the equipment. The best approach is set up the whole thing (including cables!) at your home or workplace, and dial it in as good as you can can, and then ship exactly as-is to the show, with lots of spares, test equipment, and a soldering iron.

Mix-and-match swapping in a "live" environment like a show is a prescription for a costly disaster, with good sound only attained in the last few hours of the show, when the room is nearly empty, and the press have already written their reports. How do I know? It's happened to me, and it wasn't funny at the time. The exhibitor knows better than anyone when the show is a flop ... when the Big Gamble didn't pay off the way it was hoped.

I'm surprised more exhibitors don't take along speaker measurement gear. I did, way back in the Seventies, when that kind of thing cost a lot of money. Nowadays, you can buy slick little apps like SignalScope Pro, that runs on an iDevice, using either the internal microphone (corrected by SSP), or an external pro calibrated microphone.

Gary and I had the app on our respective iPhones, and while it didn't tell us much on music, you could still see general trends from room to room. You want to look like a total geek, run an FFT when you're at a demo. It does attract attention. Also good for confirming that yes, the restaurant really is 95 dB loud, and maybe you need to protect your ears.

Mix-and-match swapping in a "live" environment like a show is a prescription for a costly disaster, with good sound only attained in the last few hours of the show, when the room is nearly empty, and the press have already written their reports. How do I know? It's happened to me, and it wasn't funny at the time. The exhibitor knows better than anyone when the show is a flop ... when the Big Gamble didn't pay off the way it was hoped.

I'm surprised more exhibitors don't take along speaker measurement gear. I did, way back in the Seventies, when that kind of thing cost a lot of money. Nowadays, you can buy slick little apps like SignalScope Pro, that runs on an iDevice, using either the internal microphone (corrected by SSP), or an external pro calibrated microphone.

Gary and I had the app on our respective iPhones, and while it didn't tell us much on music, you could still see general trends from room to room. You want to look like a total geek, run an FFT when you're at a demo. It does attract attention. Also good for confirming that yes, the restaurant really is 95 dB loud, and maybe you need to protect your ears.

Last edited:

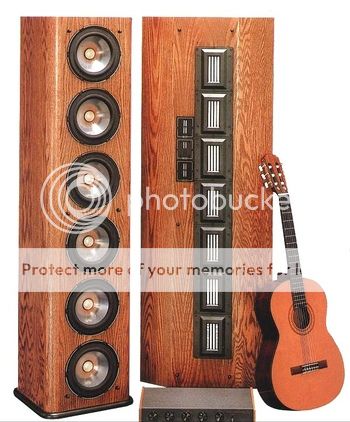

I hadn't heard the Betas before, but I have heard my friend's RS-1B's countless times, which don't sound nasal at all. This is what they look like:

Not that is pure audiophile porn.

I am left with the assumption that the recording was to blame. I was disappointed by the experience not only because I had anticipated a spectacular-sounding demo, but because it left me feeling as if the way orchestral instruments really sound has become a foreign concept to so many.

I believe that designers of audio equipment should have a highly-developed sense of what their results should sound like with various types of music. If they are in control of the program material used for their demonstrations, the results are a reflection of their level of sonic discernment. Of course, all bets are off when visitors bring their own recordings.

Gary Dahl

I think that problem is more common than we might think. I like orchestral music, but I have never had the opportunity to hear a live orchestra, so I would probably also not hear if the strings sounded nasal. I suspect a lot of demo recordings are chosen for their WOW factor, more than for the tone. Sad, but true methinks.

Deon

You hear a live orchestra (in a good hall) just once, and you realize just how awful most recordings are. It's not an easy sound to capture, with so much going on at once, and the sheer beauty of the tone is the hardest thing to capture of all. The better the player, the more astonishing and subtle the tone becomes, to the point where it passes all description. These are the performances you never forget.

Many recordings and hifi systems run the sound through an uglifier with the knob turned all the way up to 11. Turning the knob down to 2 is a superhuman achievement, and very very rare, like a hole-in-one in golf. "Best Sound of Show" would be maybe 3 or 4, if the phase of the Moon is right, and the more arcane points of the Kabbala are satisfied.

Extending the analogy, "1" on the knob would be like sitting in the 15th row of the concert hall, or standing in the middle of a stone cathedral with a pipe organ and full chorus. No system known or contemplated can do this.

I guess the reason I take a dim view of tweaking is that all I hear with cable, tube, and computer-audio tweaking is a change between 5.1 and 5.5. A step down to 3 will get my full attention, since the entire piece of music is now more compelling and interesting.

Many recordings and hifi systems run the sound through an uglifier with the knob turned all the way up to 11. Turning the knob down to 2 is a superhuman achievement, and very very rare, like a hole-in-one in golf. "Best Sound of Show" would be maybe 3 or 4, if the phase of the Moon is right, and the more arcane points of the Kabbala are satisfied.

Extending the analogy, "1" on the knob would be like sitting in the 15th row of the concert hall, or standing in the middle of a stone cathedral with a pipe organ and full chorus. No system known or contemplated can do this.

I guess the reason I take a dim view of tweaking is that all I hear with cable, tube, and computer-audio tweaking is a change between 5.1 and 5.5. A step down to 3 will get my full attention, since the entire piece of music is now more compelling and interesting.

Last edited:

This might provide a few clues ... Let's talk PS Audio and RMAF 2014 | General discussions and miscellaneous ramblings | Forums | PS Audio

Here are two quotes from that thread that might help (partially) explain what happened:

I stopped into the PS Audio room right after opening registration on Friday, to find Paul and the crew in the midst of recovering from the breakdown of one of the prototype new amplifiers feeding the IRS Betas (Paul had one set up for the panels and the other for the low end cabinets). Fortunately another was speeding down the highway from Bolder and showed up just in the nick of time.

I knew enough, though, not to make any real impressions on the big rig until at least the next day (what with the new amp rushed in), so on Saturday I came back up and listened. The new amp had been set up and given a good half day's playing on Friday. My friend and I chatted with Ted for a bit and I guess I had the "beta tester stink" on me, as when I asked one of the younger PS Audio crew (I'm sorry I didn't get his name) for the remotes he handed them right over. I started with Bill Evans and hesitated a bit. Everything was there bit not quite in control and a bit "disconnected". Ted was watching me and saw the look on my face in a flash. Listened to a couple of additional tunes and knew I had to wait. I won't hold you in suspense – by Sunday everything sounded very nicely integrated. I can only guess some settling in was needed for all that new gear, especially for the pinch hitter amp. This is nothing new, really; most rooms sound their best on Sunday.

It seems that even on Saturday things weren't quite right yet, and only on Sunday did the system gel.

...with good sound only attained in the last few hours of the show, when the room is nearly empty, and the press have already written their reports. How do I know? It's happened to me, and it wasn't funny at the time.

This might have been one of those times. Pity, it had promise.

But at the end of the day the report on the Maggies is what surprised me most. Maybe a case of the ever-elusive synergy- where the parts as a whole is so much more than just the sum of the individual parts. I would have loved to hear that one. My room is also small... Maybe... Or maybe not... Don't know...

It is my impression that the vast majority of consumers, audiophiles, dealers and manufacturers aren't looking for trying to get as close as possible to natural and realistic reproduction of live acoustic unamplified music. Manufacturers and dealers produce and sell what sells, which is what we see and hear mostly.

Yup, you got that right. Part of the reason that recordings, and some of the gear, from the Fifties sounds the way it does is that people back then went to a lot more live concerts, and played music at home with friends.

Karna remembers friends coming over and playing music on the piano in the parlor, and she played clarinet in the high school band.

When people hear live music several times a week, even cheap 5-tube table radios have to be balanced so they are musically acceptable, and the same applies to recordings made in that era. By modern standards, they were technically limited, but people expected recordings to sound like live music.

DeonC, PS Audio was sailing close to the wind by demoing new, untested electronics at the show. When the exhibitor has to swap gear mid-show, that means things have gone terribly wrong. In financial terms, half of that $5,000 was wasted, and some people (like me) got the wrong impression. Then again, RMAF is a fraction of the price of the CES, and it's probably a good place to show new gear to the public before you go for the big leagues at the CES.

I had some near-disasters at the CES, and they take a lot of fast footwork (involving air freight, taxi runs to the airport, and soldering irons) to fix them in the early hours of the show. When I was exhibiting, the make-or-break deadline for acceptable sound was between 10AM and noon Saturday, which entailed a few all-nighters on Friday evening. By afternoon, when the throngs (and reviewers) arrive in force, you've either got it together or you've fallen short.

If you've had a "good show" (the room works and people like it), then you and the other exhibitors can kick back on Saturday night and go party with each other, coast on a relaxed Sunday, and then go through the mammoth task of packing it all up again.

Karna remembers friends coming over and playing music on the piano in the parlor, and she played clarinet in the high school band.

When people hear live music several times a week, even cheap 5-tube table radios have to be balanced so they are musically acceptable, and the same applies to recordings made in that era. By modern standards, they were technically limited, but people expected recordings to sound like live music.

DeonC, PS Audio was sailing close to the wind by demoing new, untested electronics at the show. When the exhibitor has to swap gear mid-show, that means things have gone terribly wrong. In financial terms, half of that $5,000 was wasted, and some people (like me) got the wrong impression. Then again, RMAF is a fraction of the price of the CES, and it's probably a good place to show new gear to the public before you go for the big leagues at the CES.

I had some near-disasters at the CES, and they take a lot of fast footwork (involving air freight, taxi runs to the airport, and soldering irons) to fix them in the early hours of the show. When I was exhibiting, the make-or-break deadline for acceptable sound was between 10AM and noon Saturday, which entailed a few all-nighters on Friday evening. By afternoon, when the throngs (and reviewers) arrive in force, you've either got it together or you've fallen short.

If you've had a "good show" (the room works and people like it), then you and the other exhibitors can kick back on Saturday night and go party with each other, coast on a relaxed Sunday, and then go through the mammoth task of packing it all up again.

Last edited:

A more offbeat method is taking a cue from AudioKinesis and use up-firing driver(s) to floodlight the ceiling with spectrally shaped HF content. It seemed to work for Duke at the Rocky Mountain show; there was no impairment of image quality that I could hear (at least in a show setting), and the spatial impression opened up quite substantially, so the system sounded more like an electrostat.

Quote from Lynn (highlite my edit)

Thank you for this. This is the true culmination point of this thread. A highly respected authority opens up and confesses that a flooder actually improves the sound.

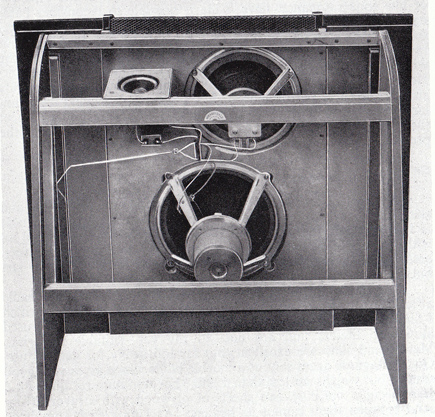

This ceiling firing tweeter method is very old. Earliest I have came across is from G.A.Briggs, the SFB/3.

Surely this should be well known, but extremely rarely executed in modern designs.

I only wonder why... Because it works very well in normal domestic rooms.

Sorry for the OT, but I have a few burning questions regarding the flooders used by AudioKinesis:

1. Was it only HF content? Or would a fullrange flooder be better?

2. What does 'spectrally shaped HF content' mean?

3. Would this work with an open-baffle speaker?

Thanks,

Deon

Sorry for the OT, but I have a few burning questions regarding the flooders used by AudioKinesis:

1. Was it only HF content? Or would a fullrange flooder be better?

2. What does 'spectrally shaped HF content' mean?

3. Would this work with an open-baffle speaker?

Thanks,

Deon

Everyone has a different take on appropriate directivity vs frequency. Monopoles (direct-radiator closed boxes and vented boxes) are close to omnidirectional around 100~200 Hz, but things usually get more directional above that. At crossover, the midwoofer approaches 90 degrees, and the combined radiation from the summed output of the woofer and the MF/HF driver narrows it further (in the vertical plane).

"Constant-directivity" horns (smoothed conicals, Quadratic Throat, OSWG's) typically radiate over a 90-degree cone, which is several times more directional that the direct-radiator woofer pattern in the 100~200 Hz range. Traditional exponentials, Tractrix, and the LeCleac'h horns steadily increase directivity as frequency increases, and can be as narrow as 30 degrees (or less) at 10 kHz.

Both fabric and metal domes radiate into a hemisphere at the crossover frequency, and like traditional horns, become more directional as frequency increases. At frequencies of 10 kHz and higher, they have broader dispersion than traditional horns, but not as broad as modern constant-directivity horn or waveguides. On the flip side of the coin, they don't usually require equalization in the passband.

Net result, most loudspeakers are more directional at HF than they are at LF, and they are aligned for flat response on-axis. This means total power into a sphere (or the room) has a falling characteristic, with some ripple in directivity around the crossover frequency. The FR of each of the first reflections (floor, ceiling, front wall, nearest side wall, and the two-bounce images) is very different than the on-axis response, and the later multi-bounce reflections are different as well. Is this ideal for music, particularly music that relies on a strong ambient impression of a hall space? That's where disagreement comes in.

I take a stance that if wider dispersion is chosen in the MF and HF region, it shouldn't be at the expense of first-arrival transient integrity. Even though the off-axis radiation of the "flooder" drivers might be 20 dB down compared to the first-arrival sound, I feel it should still be time-aligned with the first-arrival sound. I go to some trouble to suppress diffraction, and that's usually 6~20 dB lower than the direct sound from the drivers.

There's a little measurement trick I shared with Duke LeJeune at the RMAF. When you do an FFT, it's typical to use damping to absorb the floor bounce, and then set the measurement window between 4 to 7 mSec, setting the gate just before another reflection arrives. That's the basis for computing the first-arrival frequency response.

You can also measure an equivalent to a real-time analyzer (RTA) by opening the time domain out to 100 mSec, and applying 1/3 or 1/6th octave smoothing to the computed FR. That basically gets all the room reflections, along with the direct sound.

This is all standard stuff. What I told Duke was a minor variation; when you make the long-duration 100 mSec measurement, deliberately leave out the direct-sound; that is, start the gate between 3 and 5 mSec after the first sound, and let it run out to 100 mSec. This omits the direct sound, but captures all of the room reflections.

You can then overlay the FR charts for the direct-sound and the summed room reflections, and see where they diverge. By looking at the divergence between the two curves, you can then apply equalization to the "flooder" drivers to get the two curves more closely aligned. In effect, you're changing the overall spectra of the summed room reflections so they're a better match for the on-axis sound. This should make the ambient impression more true-to-life, and less like a loudspeaker.

With music that doesn't rely on ambient impression (jazz in small performing spaces, or rock with sparse reverb), matching the direct and overall room spectra may not matter that much. But for music where the impression of space is an integral part of the performance, it can matter a great deal.

Last edited:

Note that the up-firing tweeter for the G.A.Briggs SFB/3 looks pretty well time-aligned, a few inches behind the front baffle, which is where it should be. What's old is new again ... but then again, acoustics and perception haven't changed since the SFB/3 first came out, so whatever was good in the design still applies today.

Circling back to the "Beyond" project, one appeal of a more even room curve, or at least one that isn't dark in the 10 kHz and above region, is the requirement for flat on-axis response in the 5~15 kHz region is a bit relaxed. A little bit of HF rolloff may not matter if the room is well-illuminated at the same frequencies.

Although the direct, on-axis spectra dominates the overall impression of balance, the room spectra (from all the reflections) also contributes, and plays a large role in ambient impression.

Duke's little A/B comparison (switching the upward-facing "flooders" on and off) at the RMAF confirmed what I already suspected; the apparent spectral balance didn't change much, but the spatial "size" of the ambience became much larger, growing from a straight line between the speakers to larger than the room itself, with no change in the spatial locations of the instruments. If anything, they were more firmly located in space, since you could more easily separate the wash of reverb from the instruments.

Circling back to the "Beyond" project, one appeal of a more even room curve, or at least one that isn't dark in the 10 kHz and above region, is the requirement for flat on-axis response in the 5~15 kHz region is a bit relaxed. A little bit of HF rolloff may not matter if the room is well-illuminated at the same frequencies.

Although the direct, on-axis spectra dominates the overall impression of balance, the room spectra (from all the reflections) also contributes, and plays a large role in ambient impression.

Duke's little A/B comparison (switching the upward-facing "flooders" on and off) at the RMAF confirmed what I already suspected; the apparent spectral balance didn't change much, but the spatial "size" of the ambience became much larger, growing from a straight line between the speakers to larger than the room itself, with no change in the spatial locations of the instruments. If anything, they were more firmly located in space, since you could more easily separate the wash of reverb from the instruments.

Last edited:

Back in 2007 or 08, I had a chance to hear Lew Hardy's wonderful Vivaldi Audio "Academy" loud speakers, which used two horn-loaded Lowther drivers per cabinet. Those were perhaps some of the best speakers I've ever heard...period! They also had some of the very finest cabinet work I've ever seen. Lou had done some development on these and added a Visaton super tweeter and a.........Crossover/filter (Gasp!)...designed by Dan Wiggins!

Driven by a pair of Bottlehead 2A3 SET amps they shook the large room we held the DIY exhibition in, with the Drum Song on a Test Disc! The speakers were well out in the room, away from any walls or corners...Amazing!!

Here you are:

http://www.6moons.com/audioreviews/vivaldi/academy.html

Best Regards,

TerryO

Driven by a pair of Bottlehead 2A3 SET amps they shook the large room we held the DIY exhibition in, with the Drum Song on a Test Disc! The speakers were well out in the room, away from any walls or corners...Amazing!!

Here you are:

http://www.6moons.com/audioreviews/vivaldi/academy.html

Best Regards,

TerryO

Last edited:

TerryO, are those Academys the speakers that showed up for a gathering at Adire Audio headquarters? I don't remember the year but it was about the same period that the CSS FR125/WR125 were making a big splash, Kevin Haskins had one or two of his early designs there and Adire was showing their big horizontal "LCR" monitors.

TerryO, are those Academys the speakers that showed up for a gathering at Adire Audio headquarters? I don't remember the year but it was about the same period that the CSS FR125/WR125 were making a big splash, Kevin Haskins had one or two of his early designs there and Adire was showing their big horizontal "LCR" monitors.

Lew was going to show up at the Audio Club one time, but something came up and he couldn't make it. The time when he really pulled out the stops was at an event we held on Vashon Island. For some reason I seem to remember that there was another time as well, but it just won't jell in my mind!

Best Regards,

Terry

Everyone has a different take on appropriate directivity vs frequency. Monopoles (direct-radiator closed boxes and vented boxes) are close to omnidirectional around 100~200 Hz, but things usually get more directional above that. At crossover, the midwoofer approaches 90 degrees, and the combined radiation from the summed output of the woofer and the MF/HF driver narrows it further (in the vertical plane).

"Constant-directivity" horns (smoothed conicals, Quadratic Throat, OSWG's) typically radiate over a 90-degree cone, which is several times more directional that the direct-radiator woofer pattern in the 100~200 Hz range. Traditional exponentials, Tractrix, and the LeCleac'h horns steadily increase directivity as frequency increases, and can be as narrow as 30 degrees (or less) at 10 kHz.

Both fabric and metal domes radiate into a hemisphere at the crossover frequency, and like traditional horns, become more directional as frequency increases. At frequencies of 10 kHz and higher, they have broader dispersion than traditional horns, but not as broad as modern constant-directivity horn or waveguides. On the flip side of the coin, they don't usually require equalization in the passband.

Net result, most loudspeakers are more directional at HF than they are at LF, and they are aligned for flat response on-axis. This means total power into a sphere (or the room) has a falling characteristic, with some ripple in directivity around the crossover frequency. The FR of each of the first reflections (floor, ceiling, front wall, nearest side wall, and the two-bounce images) is very different than the on-axis response, and the later multi-bounce reflections are different as well. Is this ideal for music, particularly music that relies on a strong ambient impression of a hall space? That's where disagreement comes in.

I take a stance that if wider dispersion is chosen in the MF and HF region, it shouldn't be at the expense of first-arrival transient integrity. Even though the off-axis radiation of the "flooder" drivers might be 20 dB down compared to the first-arrival sound, I feel it should still be time-aligned with the first-arrival sound. I go to some trouble to suppress diffraction, and that's usually 6~20 dB lower than the direct sound from the drivers.

There's a little measurement trick I shared with Duke LeJeune at the RMAF. When you do an FFT, it's typical to use damping to absorb the floor bounce, and then set the measurement window between 4 to 7 mSec, setting the gate just before another reflection arrives. That's the basis for computing the first-arrival frequency response.

You can also measure an equivalent to a real-time analyzer (RTA) by opening the time domain out to 100 mSec, and applying 1/3 or 1/6th octave smoothing to the computed FR. That basically gets all the room reflections, along with the direct sound.

This is all standard stuff. What I told Duke was a minor variation; when you make the long-duration 100 mSec measurement, deliberately leave out the direct-sound; that is, start the gate between 3 and 5 mSec after the first sound, and let it run out to 100 mSec. This omits the direct sound, but captures all of the room reflections.

You can then overlay the FR charts for the direct-sound and the summed room reflections, and see where they diverge. By looking at the divergence between the two curves, you can then apply equalization to the "flooder" drivers to get the two curves more closely aligned. In effect, you're changing the overall spectra of the summed room reflections so they're a better match for the on-axis sound. This should make the ambient impression more true-to-life, and less like a loudspeaker.

With music that doesn't rely on ambient impression (jazz in small performing spaces, or rock with sparse reverb), matching the direct and overall room spectra may not matter that much. But for music where the impression of space is an integral part of the performance, it can matter a great deal.

Thanks, Lynn. That gives me a lot to think about. I really appreciate the detailed post. It makes me think one should have such a tweeter, but connected to a MiniDSP unit so you can adjust the HF content to suit the music being played. Challenging, but fun.

With music that doesn't rely on ambient impression (jazz in small performing spaces, or rock with sparse reverb), matching the direct and overall room spectra may not matter that much. But for music where the impression of space is an integral part of the performance, it can matter a great deal.

I had a friend in NJ that did his own variation on Ambiophonics with lots of surrounds built into an otherwise dead room. We listened to a lot of music, lots of choral and orchestral, some opera and a bunch of rock (even live). For music recorded in a hall it is a pretty stark improvement in believability. Even rock music such as Cowboy Junkies recorded in a church. Studio albums and even live rock recordings (Roger Waters iirc) I felt it added nothing.

For me, I felt it was too much of an effort and impracticality for something that adds only to a minority of my listening. If I listened to primarily orchestral music, I'd probably seek to continue down that rabbit hole.

- Home

- Loudspeakers

- Multi-Way

- Beyond the Ariel