Hello everyone,

I'm currently trying to build a Car Amplifier SMPS based on something like SG3525 and am reading through lots of threads and webpages. I found the following statement on this site:

I'm going to use a toroidal Amidon core called "FR 140-77" for my first experiments. The datasheet shows a graph called "Flux Density vs. Temperature" which reads something like this:

4800 gauss @ 25 celsius

4500 gauss @ 50 celsius

4200 gauss @ 75 celsius

3700 gauss @ 100 celsius

3300 gauss @ 125 celsius

Measured on an 18/10/6mm toroid at 10kHz and H=5 oersted

Those numbers are quite a bit more than the stated 2000 gauss on the aforementioned webpage.

The question is, what flux density should I calculate with? And why?

Is 2000 generally a good assumption to go with? Or is it safe to go for 4000 and hoping the core will not begin to glow and heat above 75 celsius ?

?

Thanks in advance,

Lasse

I'm currently trying to build a Car Amplifier SMPS based on something like SG3525 and am reading through lots of threads and webpages. I found the following statement on this site:

Generally, in car audio amplifier switching power supplies operating at or below 35.000hz, the flux density is kept at or below 2000 gauss. Some cores will operate at higher flux density for frequencies below 35,000hz but 2000 gauss is a good conservative number. For higher frequencies, you have to design for lower flux density to prevent excess core heating.

I'm going to use a toroidal Amidon core called "FR 140-77" for my first experiments. The datasheet shows a graph called "Flux Density vs. Temperature" which reads something like this:

4800 gauss @ 25 celsius

4500 gauss @ 50 celsius

4200 gauss @ 75 celsius

3700 gauss @ 100 celsius

3300 gauss @ 125 celsius

Measured on an 18/10/6mm toroid at 10kHz and H=5 oersted

Those numbers are quite a bit more than the stated 2000 gauss on the aforementioned webpage.

The question is, what flux density should I calculate with? And why?

Is 2000 generally a good assumption to go with? Or is it safe to go for 4000 and hoping the core will not begin to glow and heat above 75 celsius

Thanks in advance,

Lasse

Those are saturation flux density. You don't want to operate near saturation. At higher flux density, the core loss is greater which makes the core run hotter. From THIS datasheet (page 18), you can see that the loss increases above 60C. When you combine heating from ambient (as high as 55C in the trunk of a vehicle) plus heating from core losses (deteremined by flux density) plus heating from copper losses (due to the current flowing through the resistance of the wire), you can see that it's important to use a relatively conservative flux density in the design.

You may also be interested in page 109 of the site.

You may also be interested in page 109 of the site.

That's the achievable flux density at a given temperature for a given magnetizing field strength per metre. So you're going to to anticipate the operating temperature and consequent flux density on the basis of the magnetising field strength per metre. The permeability changes with temperature. The estimation process is complicated by the fact that the operation of the core itself causes the heating for the reasons given by Perry. More current causes more heating which tends to reduce the flux density, which calls for more current.

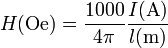

The Oersted is the mmf, magneto-motive force, or magnetising field strength per unit length established by a single winding wire loop:

Where l is the path length, or average circumference of the core in metres. You would commonly work in ampere-turns per metre.

To put it another way, the Oersted is 1000/(4*pi), approx 79.6, ampere-turns per metre.

So you can establish 3300 gauss @ 125 celcius with ~400 ampere-turns/metre. Since the core has a circumference of 18 mm, this equates to (18*400)/1000 = 7.2 ampere-turns or 72 turns carrying 0.1 amp.

2000 gauss @ 125 celcius would be 2000/3300 * 7.2 = 4.36 ampere-turns.

w

If I haven't slipped a cog again. If I have, I'm sure someone will correct me.

The terms used for these quantities are not entirely consistent from author to author.

The Oersted is the mmf, magneto-motive force, or magnetising field strength per unit length established by a single winding wire loop:

Where l is the path length, or average circumference of the core in metres. You would commonly work in ampere-turns per metre.

To put it another way, the Oersted is 1000/(4*pi), approx 79.6, ampere-turns per metre.

So you can establish 3300 gauss @ 125 celcius with ~400 ampere-turns/metre. Since the core has a circumference of 18 mm, this equates to (18*400)/1000 = 7.2 ampere-turns or 72 turns carrying 0.1 amp.

2000 gauss @ 125 celcius would be 2000/3300 * 7.2 = 4.36 ampere-turns.

w

If I haven't slipped a cog again. If I have, I'm sure someone will correct me.

The terms used for these quantities are not entirely consistent from author to author.

Yuck, non-SI units...

MMF is amperes. Oersted (or A/m for SI units) is magnetization (magnetic field intensity), not magnetomotive force.

Lots of datasheets give parameters in mm^2, so it's very easy to work with derived SI units. In that case:

(Using capital 'L' for magnetic path length, since 'l' looks bad.)

H is in A/m

B is in T == Wb/m^2 == V.s/m^2

Phi = B*A is in uWb when A is in mm^2

Phi = V * dt for a square pulse, in uWb when dt is in microseconds.

H = N*I / L is in A/mm when L is in mm

mu_0 is 1.256 x 10^-6 H/m, or 1.256 nH/mm

A_L = mu_0*A_e / L_e is in nH/t^2 when A_e is in mm^2 and L_e is in mm, using mu_0 = 1.256 nH/mm

In general, small to medium ferrites can be run at any desired flux density. The loss is way, way lower than powdered iron (at the same Bmax!). You'll most likely never notice it. Conduction and eddy current loss in the copper will dominate. Thus, you want to set flux density to whatever the safe value is.

At high frequencies (over 200kHz, depending on ferrite type), loss becomes significant and lower flux densities are desirable.

At higher powers (over 500W), power dissipation becomes a problem, and even at moderate frequencies (~100kHz), a lower flux density is desirable to reduce maximum hotspot temperatures.

There are a few power ferrite mixes which actually have lower losses and higher permeability at high temperature. If you're making a big transformer, such a mix might be desirable to reduce hot-spot temperatures. (It's like PTC resistors in parallel!) Saturation generally has a negative tempco; I forget if any are positive (until the curie temperature that is).

For full-wave inverters (half and full bridge), you can safely reach 0.4T near saturation (when cold). You want this to occur when more than a full half cycle's worth of flux is applied, because when the power supply turns on (assuming no soft start, which IS a nice feature to have), it will start with a full width pulse, which unbalances the flux. After the LC time constant, it will stabilize back to zero (assuming a coupling capacitor is used, e.g. half / full bridge). This ensures no saturation during startup.

In steady state operation, the average flux density will be zero, with a *peak-to-peak* value corresponding to a half wave's flux. Therefore, the peak flux density in steady-state will be one-half the worst case startup flux density. This will help it run cooler, though the transformer will be somewhat larger than technically necessary.

For half-wave supplies (flyback, single/dual transistor forward, etc.), flux returns to zero during the off-time, so the peak flux is equal to the applied flux.

Tim

MMF is amperes. Oersted (or A/m for SI units) is magnetization (magnetic field intensity), not magnetomotive force.

Lots of datasheets give parameters in mm^2, so it's very easy to work with derived SI units. In that case:

(Using capital 'L' for magnetic path length, since 'l' looks bad.)

H is in A/m

B is in T == Wb/m^2 == V.s/m^2

Phi = B*A is in uWb when A is in mm^2

Phi = V * dt for a square pulse, in uWb when dt is in microseconds.

H = N*I / L is in A/mm when L is in mm

mu_0 is 1.256 x 10^-6 H/m, or 1.256 nH/mm

A_L = mu_0*A_e / L_e is in nH/t^2 when A_e is in mm^2 and L_e is in mm, using mu_0 = 1.256 nH/mm

In general, small to medium ferrites can be run at any desired flux density. The loss is way, way lower than powdered iron (at the same Bmax!). You'll most likely never notice it. Conduction and eddy current loss in the copper will dominate. Thus, you want to set flux density to whatever the safe value is.

At high frequencies (over 200kHz, depending on ferrite type), loss becomes significant and lower flux densities are desirable.

At higher powers (over 500W), power dissipation becomes a problem, and even at moderate frequencies (~100kHz), a lower flux density is desirable to reduce maximum hotspot temperatures.

There are a few power ferrite mixes which actually have lower losses and higher permeability at high temperature. If you're making a big transformer, such a mix might be desirable to reduce hot-spot temperatures. (It's like PTC resistors in parallel!) Saturation generally has a negative tempco; I forget if any are positive (until the curie temperature that is).

For full-wave inverters (half and full bridge), you can safely reach 0.4T near saturation (when cold). You want this to occur when more than a full half cycle's worth of flux is applied, because when the power supply turns on (assuming no soft start, which IS a nice feature to have), it will start with a full width pulse, which unbalances the flux. After the LC time constant, it will stabilize back to zero (assuming a coupling capacitor is used, e.g. half / full bridge). This ensures no saturation during startup.

In steady state operation, the average flux density will be zero, with a *peak-to-peak* value corresponding to a half wave's flux. Therefore, the peak flux density in steady-state will be one-half the worst case startup flux density. This will help it run cooler, though the transformer will be somewhat larger than technically necessary.

For half-wave supplies (flyback, single/dual transistor forward, etc.), flux returns to zero during the off-time, so the peak flux is equal to the applied flux.

Tim

MMF is amperes. Oersted (or A/m for SI units) is magnetization (magnetic field intensity), not magnetomotive force.

I didn't say it was.

'The Oersted is the mmf, magneto-motive force, or magnetising field strength per unit length'

magneto-motive force = magnetising field strength

I'm sorry if my use of English left room for some confusion. As I said: the terms used for these quantities are not entirely consistent from author to author.

Since, however, nobody has chosen to dispute the worked example, you can take what I have written as being substantially correct.

w

Thanks for your answers. As I see that whole thing is quite complex, so I think I'll stick to the 2000 gauss and move on...  .

.

I simply thought it would be good to use as much flux as possible, but how would I know how much is too much? I thought that 2000 could be a bit too conservative, since it's stated as "generally" without mentioning any core materials.

Okay. Thought I could go close to it, but as it seems it's better to have some distance to it.

Since I have read only 2 pages of your site, I'll fetch that up .

.

I'm not quite sure if I understand what that means. If I have a primary winding of 4 turns and the current through it is 1A, then the core carries 2000 gauss when it's already at 125C?

How can I judge from the datasheet? Obviously Material #77 is nothing special since it saturates at 4800 gauss @ 25C? If a theoretical datasheet of a theoretical material would read 5800@25C and behave similar to #77, would I then calculate with 2500 or even more gauss? Or would I just take advantage of the fact that the whole thing would stay cooler?

What if I calculated with only 1000 gauss? Wouldn't I waste anything?

Thanks again,

Lasse

I simply thought it would be good to use as much flux as possible, but how would I know how much is too much? I thought that 2000 could be a bit too conservative, since it's stated as "generally" without mentioning any core materials.

Those are saturation flux density. You don't want to operate near saturation.

Okay. Thought I could go close to it, but as it seems it's better to have some distance to it.

You may also be interested in page 109 of the site.

Since I have read only 2 pages of your site, I'll fetch that up

2000 gauss @ 125 celcius would be 2000/3300 * 7.2 = 4.36 ampere-turns.

I'm not quite sure if I understand what that means. If I have a primary winding of 4 turns and the current through it is 1A, then the core carries 2000 gauss when it's already at 125C?

There are a few power ferrite mixes which actually have lower losses and higher permeability at high temperature. If you're making a big transformer, such a mix might be desirable to reduce hot-spot temperatures. (It's like PTC resistors in parallel!) Saturation generally has a negative tempco; I forget if any are positive (until the curie temperature that is).

How can I judge from the datasheet? Obviously Material #77 is nothing special since it saturates at 4800 gauss @ 25C? If a theoretical datasheet of a theoretical material would read 5800@25C and behave similar to #77, would I then calculate with 2500 or even more gauss? Or would I just take advantage of the fact that the whole thing would stay cooler?

What if I calculated with only 1000 gauss? Wouldn't I waste anything?

Thanks again,

Lasse

They're the flux densities at the stated temperatures established by 5 Oersted. (from your original post). They may be saturation flux densities, but that is not clear from the information given. Typical ferrite saturation flux densities are in the range 0.3-0.5 Tesla (3000-5000 gauss) so they may well be. In the absence of any other information we have to presume that B versus H (gauss vs. oersted) is a straight line relationship. This is not in fact the case, but ferrite has a near-trapezoidal hysteresis loop, so this is not an unreasonable presumption in this case.

5 Oersted is equivalent to ~400 Ampere-turns/metre. (5 * 79.59)

The path length is 18mm. 1 metre is 1000 mm. Therefore 400*(18/1000) = 7.2 ampere turns is equivalent in your chosen core in terms of magnetising field strength per metre to 5 Oersted.

Looking again at the table:

4800 gauss @ 25 celsius

4500 gauss @ 50 celsius

4200 gauss @ 75 celsius

3700 gauss @ 100 celsius

3300 gauss @ 125 celsius

These are the values of flux density established by 7.2 ampere-turns at the stated temperatures in your core of choice. If, for example, the operating temperature were 25 celcius, then 7.2 ampere-turns would give you 4800 gauss. Since the maximum you require is 2000 gauss, then the ampere-turns required to establish this would be 2000/4800 * 7.2 = 3 ampere-turns.

Since the permeability falls with temperature then in order not to exceed 2000 gauss it is sufficient not to exceed 3 ampere-turns in any case. You need to be aware though, that if you are employing this component to construct e.g. an inductor, then the inductance is falling away as the temperature rises. The additional information in the table enables you to determine whether the inductance will fall below an acceptable level at any given temperature.

Have a look here:

Power Transformer & Inductor- Design Principles, Calculation, Software

Electric Circuits by Theodore F. Bogart, ISBN 0-70-112920-0 is a good reference book for this subject

w

5 Oersted is equivalent to ~400 Ampere-turns/metre. (5 * 79.59)

The path length is 18mm. 1 metre is 1000 mm. Therefore 400*(18/1000) = 7.2 ampere turns is equivalent in your chosen core in terms of magnetising field strength per metre to 5 Oersted.

Looking again at the table:

4800 gauss @ 25 celsius

4500 gauss @ 50 celsius

4200 gauss @ 75 celsius

3700 gauss @ 100 celsius

3300 gauss @ 125 celsius

These are the values of flux density established by 7.2 ampere-turns at the stated temperatures in your core of choice. If, for example, the operating temperature were 25 celcius, then 7.2 ampere-turns would give you 4800 gauss. Since the maximum you require is 2000 gauss, then the ampere-turns required to establish this would be 2000/4800 * 7.2 = 3 ampere-turns.

Since the permeability falls with temperature then in order not to exceed 2000 gauss it is sufficient not to exceed 3 ampere-turns in any case. You need to be aware though, that if you are employing this component to construct e.g. an inductor, then the inductance is falling away as the temperature rises. The additional information in the table enables you to determine whether the inductance will fall below an acceptable level at any given temperature.

Have a look here:

Power Transformer & Inductor- Design Principles, Calculation, Software

Electric Circuits by Theodore F. Bogart, ISBN 0-70-112920-0 is a good reference book for this subject

w

To completely disambiguate the description it is perhaps best to note that the units of mmf are amperes, and this should be distinguished from electric current which is also measured in amperes. Since 1 turn of wire carrying a current of 1 ampere produces a mmf of 1 ampere, and the effect in terms of flux density is multiplied by the number of turns, then it is commonplace to use the terms amperes and ampere-turns interchangeably when considering mmf, although mmf is properly expressed in amperes.

w

w

FYI, figuring transformer performance by ampere-turns is, at best, a misleading approach. To clarify: the amp-turns in question are magnetizing amp-turns, which is what the primary delivers. It is not the total winding current, because the secondary amp-turns substantially cancel that.

A transformer with 100 turns, delivering 10A, has 1000At per winding, but might only draw 1At magnetization. It's easy to miss if you tried measuring the parameters in real operation this way!

For transformers, flux seems much more fundamental than magnetization. This is a direct circuit quantity, easily measured for square waves, and always produces a known amount of flux (i.e., by definition!), regardless of the relative permeability of the material.

For inductors, you need to know both, since you're working within the flux limits of the material and designing for a particular bias current. (Incidentially, notice there is a "DC flux", even when the coil's voltage is zero -- this is handy to remember in calculations on filter chokes.)

Tim

A transformer with 100 turns, delivering 10A, has 1000At per winding, but might only draw 1At magnetization. It's easy to miss if you tried measuring the parameters in real operation this way!

For transformers, flux seems much more fundamental than magnetization. This is a direct circuit quantity, easily measured for square waves, and always produces a known amount of flux (i.e., by definition!), regardless of the relative permeability of the material.

For inductors, you need to know both, since you're working within the flux limits of the material and designing for a particular bias current. (Incidentially, notice there is a "DC flux", even when the coil's voltage is zero -- this is handy to remember in calculations on filter chokes.)

Tim

- Status

- This old topic is closed. If you want to reopen this topic, contact a moderator using the "Report Post" button.

- Home

- Amplifiers

- Power Supplies

- Flux Density in Car SMPS Toroid