How is uniform different from constant ?

Call me stupid but I don't understand the difference either

Can anyone please define "uniform" vs "constant"?

That makes it somewhat pointless to optimize pattern control in a region that will be blended with an adjacent source anyway.

Of course it makes sense that the radiation pattern of each driver "matches" because drivers don't blend. Each source continues to radiate as a single source and both patterns are superimposed onto each other which results in interference. Two waves of sine bursts approaching from opposite directions will still look like sine bursts after they passed through another. The wave shape isn't altered.

It's the same thingPeople simply don't use precise wording.

What kind of directivity is that ...?

it's a FCUFS' directivity

Hey, everyone, let's not start with the name calling again, there's been too much of that already and for no good reason. The OP presented a technical discussion of the relative merits of directivity control and why he likes a certain horn design (H290) rather than some others, no foul in that. No need to get religious about this stuff, it's just hifi.

Not that I necessarily agree with Wayne on all of what he said. I'd still maintain that a "5dB ripple" is really a +/-2.5dB ripple (semantics, perhaps, but 2.5dB response variation is way better than pretty much any real system, in-room). And that much ripple has to do with the baffle situation (lips overhanging, edge effects).

Some (Gedlee, QSC, SEOS) opt to avoid a sharp transition between horn and baffle which presents a diffraction source (waistbanding effect), even if mitigated by horn directivity. If the ripple in the case illustrated came from the SEOS horn being too short, why does it appear at higher frequencies above 2kHz? The horn isn't too short for 4kHz, certainly. Low frequencies don't affect high frequencies, though their responses might perhaps come from similar causes. Larger SEOS (and some go as high as 18" for 1" drivers) don't change in character from smaller ones.

As far as directivity being a "fad", as mentioned earlier in the thread, I strongly disagree. Just because a sound doesn't come directly from speaker to your ears doesn't mean it suddenly becomes inaudible -- if you turn a speaker away from you, you'll still hear it quite well, even up at the treble frequencies. Once released into the room, sounds will reflect around until dissipated, coming again and again at your ears. It can't be avoided (except outside maybe) but you can (1) attenuate it: control directivity so that off-axis is lower than on-axis and (2) make sure it's response doesn't stand out: make the stuff you send bouncing around the room have a similar response to the direct sound so it doesn't sound out of place and will be well-masked by the direct sound. IMO, nothing says "I'm a speaker!" like an off-axis high frequency peak signaling its point of origin.

An elephant in the room with the waveguides discussed above, though, is the vertical directivity response. There's pattern flip in all these asymmetric horns (though I think it's an ok tradeoff to get the drivers closer together) and there will be odd lobes firing up toward the ceiling and floor from driver interference. The floor might have some absorption from a rug (though not likely very effective at mid frequencies) but the ceiling is usually a virtual acoustic mirror giving at least one strong reflection. Having drivers close together helps limit the irregularities some, but not a lot. The only designs I know of that deal with that entirely are the Danley Synergies (and similar designs) and the big Tannoys.

Not that I necessarily agree with Wayne on all of what he said. I'd still maintain that a "5dB ripple" is really a +/-2.5dB ripple (semantics, perhaps, but 2.5dB response variation is way better than pretty much any real system, in-room). And that much ripple has to do with the baffle situation (lips overhanging, edge effects).

Some (Gedlee, QSC, SEOS) opt to avoid a sharp transition between horn and baffle which presents a diffraction source (waistbanding effect), even if mitigated by horn directivity. If the ripple in the case illustrated came from the SEOS horn being too short, why does it appear at higher frequencies above 2kHz? The horn isn't too short for 4kHz, certainly. Low frequencies don't affect high frequencies, though their responses might perhaps come from similar causes. Larger SEOS (and some go as high as 18" for 1" drivers) don't change in character from smaller ones.

As far as directivity being a "fad", as mentioned earlier in the thread, I strongly disagree. Just because a sound doesn't come directly from speaker to your ears doesn't mean it suddenly becomes inaudible -- if you turn a speaker away from you, you'll still hear it quite well, even up at the treble frequencies. Once released into the room, sounds will reflect around until dissipated, coming again and again at your ears. It can't be avoided (except outside maybe) but you can (1) attenuate it: control directivity so that off-axis is lower than on-axis and (2) make sure it's response doesn't stand out: make the stuff you send bouncing around the room have a similar response to the direct sound so it doesn't sound out of place and will be well-masked by the direct sound. IMO, nothing says "I'm a speaker!" like an off-axis high frequency peak signaling its point of origin.

An elephant in the room with the waveguides discussed above, though, is the vertical directivity response. There's pattern flip in all these asymmetric horns (though I think it's an ok tradeoff to get the drivers closer together) and there will be odd lobes firing up toward the ceiling and floor from driver interference. The floor might have some absorption from a rug (though not likely very effective at mid frequencies) but the ceiling is usually a virtual acoustic mirror giving at least one strong reflection. Having drivers close together helps limit the irregularities some, but not a lot. The only designs I know of that deal with that entirely are the Danley Synergies (and similar designs) and the big Tannoys.

An elephant in the room with the waveguides discussed above, though, is the vertical directivity response. There's pattern flip in all these asymmetric horns (though I think it's an ok tradeoff to get the drivers closer together) and there will be odd lobes firing up toward the ceiling and floor from driver interference. The floor might have some absorption from a rug (though not likely very effective at mid frequencies) but the ceiling is usually a virtual acoustic mirror giving at least one strong reflection. Having drivers close together helps limit the irregularities some, but not a lot. The only designs I know of that deal with that entirely are the Danley Synergies (and similar designs) and the big Tannoys.

a coincident FCUFS does it too, no "odd lobes firing up toward the ceiling and floor from driver interference"

It's not a crusade against anyone. This is a technical discussion. One that I would appreciate nobody derail into name calling, or turning it into something personal.

Well, I'm clearly not the only person who read what you actually wrote (as well as the graph labels) and drew that inference...

Bearing all that in mind, what do you think of the idea that I've proposed? Do you think a home hifi waveguide should be optimized for smoothness or for pattern control?

Honestly, probably pattern control. The reason being that the pattern is determined by physics and geometry, but if the pattern is fairly uniform over a wide axis, then FR can be controlled with passive/active EQ.

Furthermore, I look at that SEOS graph and I see that a large bit of the variation is a broad peak at 4kHz or so. Assuming that carries through the pattern, basically just one parametric filter will knock that down all over.

Note: no dog in this hunt. I greatly admire what both of you are doing. And went in an entirely different direction (TAD/Pioneer 5" concentric for mids/highs up front in a 3-way + flanking sub setup, 5" KEF Uni-Q's for side and rear surrounds) for my own use. Though I am, admittedly, considering picking up a set of the new plastic SEOS15's, to use with 12" woofers.

1. On axis linearity

2. Distortion performance

3. Phase integration

4. Off axis Linearity

That's where I see uniform directivity falling on the order of importance. You can obviously have a great sounding speaker without it...

That is the opposite of my experience. Speakers with midband pattern discontinuities invariably sound wrong to me.

This is a simple generalization and doesn't apply to every situation, or speaker. A few db more energy greater then 45 degrees off axis between 2-4 khz does not magically take over the entire room when you are listening to the on axis sound of the speakers... This idea is just getting ridiculous

Only in the extreme nearfield is one listening to the "on axis sound of the speakers."

IMO, nothing says "I'm a speaker!" like an off-axis high frequency peak signaling its point of origin.

I'd think a "off-axis high frequency peak" would signal our brain "Me (reflection) is the real source and not that speaker".

The other day I was standing on a small airfield with a small plane making its way to the runway. Suddenly the sound of another plane grabbed my attention. When I turned my head there was the closed hangar. What I heard was a reflection bouncing off the hangar door.

And it is all achievable with:

You should give that thing its own thread.

Well, I'm clearly not the only person who read what you actually wrote (as well as the graph labels) and drew that inference...

Honestly, probably pattern control. The reason being that the pattern is determined by physics and geometry, but if the pattern is fairly uniform over a wide axis, then FR can be controlled with passive/active EQ.

Furthermore, I look at that SEOS graph and I see that a large bit of the variation is a broad peak at 4kHz or so. Assuming that carries through the pattern, basically just one parametric filter will knock that down all over.

Note: no dog in this hunt. I greatly admire what both of you are doing. And went in an entirely different direction (TAD/Pioneer 5" concentric for mids/highs up front in a 3-way + flanking sub setup, 5" KEF Uni-Q's for side and rear surrounds) for my own use. Though I am, admittedly, considering picking up a set of the new plastic SEOS15's, to use with 12" woofers.

That is the opposite of my experience. Speakers with midband pattern discontinuities invariably sound wrong to me.

Only in the extreme nearfield is one listening to the "on axis sound of the speakers."

Are the speakers in a empty room, being equal distance from every boundary? I'm guessing no. At this point your room is not giving you a constant level of reflected sound.

I'm going to bow out before I stir up to many more fanatics....

The room and controlling reflections in a small room is the issue, as pointed out earlier the ceiling, floor and sidewall reflections are issues here, ideally if one controls the first reflections so they are >= 10ms and they reflections are reduced in amplitude a lot of 'problems with speakers disappear.

This seems to me to be one advantage of a well designed floor speaker. Another example is an electrostat, which can have a controlled dispersion as long as it isn't placed closer that 4 ft from a wall.

This seems to me to be one advantage of a well designed floor speaker. Another example is an electrostat, which can have a controlled dispersion as long as it isn't placed closer that 4 ft from a wall.

In Toole's book, Chapters 18 and 19 are very important. He emphasizes smoothness of response over flatness. Also, no particular directivity was preferred in the blind tests. Of the two loudspeakers receiving the highest ratings, one is a conventional direct radiator and another is a horn. So, again, no particular directivity was preferred.

That being said, matching the direcitivty of the drivers near the crossover is a good thing. Peaks in the power response are audible and not good. But beyond that, having constant directivity through the entire spectrum is not necessary. This is what I was calling a fad. Not directivity itself. I like directivity. It allows you to point the sound where you want it to go. I personally own SEOS-12 and SEOS-18 and like them both. In my room, it creates a more believable image. But it's not because they have constant directivity, it is because early reflections are avoided.

What Wayne seems to be saying does have some validity, in that smoothness should be optimized over pattern control. A somewhat narrowing beamwidth is just fine, but ripples in the response are not good. Like Bill said, I don't think the ripples are 5db, and to me at least, there doesn't appear to be much difference in the two waveguides.

That being said, matching the direcitivty of the drivers near the crossover is a good thing. Peaks in the power response are audible and not good. But beyond that, having constant directivity through the entire spectrum is not necessary. This is what I was calling a fad. Not directivity itself. I like directivity. It allows you to point the sound where you want it to go. I personally own SEOS-12 and SEOS-18 and like them both. In my room, it creates a more believable image. But it's not because they have constant directivity, it is because early reflections are avoided.

What Wayne seems to be saying does have some validity, in that smoothness should be optimized over pattern control. A somewhat narrowing beamwidth is just fine, but ripples in the response are not good. Like Bill said, I don't think the ripples are 5db, and to me at least, there doesn't appear to be much difference in the two waveguides.

Last edited:

Let me take a monent to say again that I think the SEOS device(s) are useful and interesting and the guys that design with them are great guys. Many of them are friends of mine, and I regret that any animosity developed. I honestly don't feel any ill-will for the designers, we've always been sort of kindred spirits. There are probably other reasons for the rift, and as long as we keep things technical, those do not develop.

I sort of take my lead from Keele's work on CD horns, where he describes horns with the "right size" mouth. The ripple is set by a lot of factors, and while one can generally assume that the larger the mouth, the less ripple there will be - that is not always true. Combine that understanding with a catenary flare to reduce internal reflections and the horn loses its throat diffraction but still acts a lot like the CD horns Keele described.

Beyond that, in my experience with horns, one easy way to get a "horn honk" sound is from standing waves. Pipe modes in the crossover region really make a "cupped hands" horn sound, especially if their impedance peak is manifested in the response curve. That's why I was always so focused on damping - It's like a mantra in my "Crossover Electronics 101" seminar and all my other crossover documents.

I demonstrate this kind of peaking during the talk by showing different crossovers, some that are more vulnerable to impedance peaks and create an audible response peak. We play music through these crossovers and waveguides, and I flip a switch to compare one crossover that can damp the modes with another that cannot. The attendees of the seminar all hear it, as they see it on the transfer function on the overhead projector.

So this is a big focus of mine, and I try to limit those 5dB peaks and valleys because I can really hear them. I do realize that the designers will remove any peaks they see in the response curve using notch circuits. I think that's valid and important. But to me, I try to make the horn flat, and then try to damp it appropriately in the crossover too. It is very important that the system response not have 5dB peaks and valleys in the 1kHz to 4kHz region, because that's right at the apex of the Fletcher-Munson curve where we are all most sensitive. Peaks there stand out there with annoying strength, and I believe that is the think most responsible for what some would call "horn honk."

The diffraction slot in the throat of an constant-directivity horn makes an unnatural treble sound, I think. I've heard some call it "spitty" or "splashy", sort of like the fake cymbals in a drum machine. I don't like that sound either, but I don't describe it as horn honk. I think what people object to as horn honk is a standing wave thing. So I seek to mimimize that in my designs.

I agree with many of you that the words "uniform" and "constant" are somewhat synonymous, and that's why I chose to use "uniform directivity" to describe what I mean. I wanted it to have a similar connotation, but to not use the phrase "constant directivity", which had already been defined in the literature to mean beamwidth that doesn't change with frequency.

Collapsing directivity is a phrase I've often heard to describe a source that has beamwidth that narrows proportional to frequency.

Matched-directivity speakers have collapsing directivity up to the crossover point, and then constant directivity above that. I dunno, it's smooth, and it seems useful, so I just started calling that "uniform directivity." I like using that phrase to me "almost constant directivity." But that's just my nomenclature, and I usually try to describe what I mean as well.

"Blending" is another term I use that really just means summing. I think I borrowed this one from Earl Geddes though. I liked it because it gives the right "feel." He used it when describing the complex summing that occurs when subs and mains are overlapped in the modal region. Im some positions in the room, the summing is constructive, others it is not. Same with the room modes and reflections. This is nicely described as "blending", in my opinion, and so I borrowed his informal terminology.

In the crossover region, the summing isn't nearly as complex as it is in the modal region of a room. But it does have constructive summing in some positions and destructive summing in other positions. The forward lobe is made of constructively summed wavefronts, which then combine to make a nice clean primary lobe.

Movement along the vertical axis creates a path length difference between the listener and the sources. At some point, the summing moves from constructive towards destructive interference. So movement along the vertical plane eventually brings the listener to the edge of the forward lobe, and into the vertical null, where summing is destructive. Then outside these, secondary lobes form. The secondary lobe forms where path length differences create a full cycle shift. If the individual source beamwidths are narrow enough, the secondary lobes will be small. If source beamwidths are large, the secondary lobes will be also.

Movement along the horizontal axis does not create a path length difference, except that caused by the source area, the very reason that the midwoofer becomes directional in the first place. But there is no path length difference change between acoustic centers. So summing is generally constructive out to fairly large angles, where the directivity of the piston sets in. There summing becomes complex, something like the situation with the verticals. So the edge of the pattern in the horizontal is usually a little bit lumpy through the crossover region as a result.

That's why I describe the combined output of the two sources in the overlap region as being "blended." It's also why I like to match their directivities as much as possible, by choosing crossover where the beamwidths of the two subsystems match. I have seen some describe pushing the crossover point so low directivity "matching" is effectively done down where both sources radiation patterns approach omnidirectional. I think this is a bad practice, both because of the summing/blending thing I just described and also because compression drivers are strained when running them too low.

I sort of take my lead from Keele's work on CD horns, where he describes horns with the "right size" mouth. The ripple is set by a lot of factors, and while one can generally assume that the larger the mouth, the less ripple there will be - that is not always true. Combine that understanding with a catenary flare to reduce internal reflections and the horn loses its throat diffraction but still acts a lot like the CD horns Keele described.

Beyond that, in my experience with horns, one easy way to get a "horn honk" sound is from standing waves. Pipe modes in the crossover region really make a "cupped hands" horn sound, especially if their impedance peak is manifested in the response curve. That's why I was always so focused on damping - It's like a mantra in my "Crossover Electronics 101" seminar and all my other crossover documents.

I demonstrate this kind of peaking during the talk by showing different crossovers, some that are more vulnerable to impedance peaks and create an audible response peak. We play music through these crossovers and waveguides, and I flip a switch to compare one crossover that can damp the modes with another that cannot. The attendees of the seminar all hear it, as they see it on the transfer function on the overhead projector.

So this is a big focus of mine, and I try to limit those 5dB peaks and valleys because I can really hear them. I do realize that the designers will remove any peaks they see in the response curve using notch circuits. I think that's valid and important. But to me, I try to make the horn flat, and then try to damp it appropriately in the crossover too. It is very important that the system response not have 5dB peaks and valleys in the 1kHz to 4kHz region, because that's right at the apex of the Fletcher-Munson curve where we are all most sensitive. Peaks there stand out there with annoying strength, and I believe that is the think most responsible for what some would call "horn honk."

The diffraction slot in the throat of an constant-directivity horn makes an unnatural treble sound, I think. I've heard some call it "spitty" or "splashy", sort of like the fake cymbals in a drum machine. I don't like that sound either, but I don't describe it as horn honk. I think what people object to as horn honk is a standing wave thing. So I seek to mimimize that in my designs.

I agree with many of you that the words "uniform" and "constant" are somewhat synonymous, and that's why I chose to use "uniform directivity" to describe what I mean. I wanted it to have a similar connotation, but to not use the phrase "constant directivity", which had already been defined in the literature to mean beamwidth that doesn't change with frequency.

Collapsing directivity is a phrase I've often heard to describe a source that has beamwidth that narrows proportional to frequency.

Matched-directivity speakers have collapsing directivity up to the crossover point, and then constant directivity above that. I dunno, it's smooth, and it seems useful, so I just started calling that "uniform directivity." I like using that phrase to me "almost constant directivity." But that's just my nomenclature, and I usually try to describe what I mean as well.

"Blending" is another term I use that really just means summing. I think I borrowed this one from Earl Geddes though. I liked it because it gives the right "feel." He used it when describing the complex summing that occurs when subs and mains are overlapped in the modal region. Im some positions in the room, the summing is constructive, others it is not. Same with the room modes and reflections. This is nicely described as "blending", in my opinion, and so I borrowed his informal terminology.

In the crossover region, the summing isn't nearly as complex as it is in the modal region of a room. But it does have constructive summing in some positions and destructive summing in other positions. The forward lobe is made of constructively summed wavefronts, which then combine to make a nice clean primary lobe.

Movement along the vertical axis creates a path length difference between the listener and the sources. At some point, the summing moves from constructive towards destructive interference. So movement along the vertical plane eventually brings the listener to the edge of the forward lobe, and into the vertical null, where summing is destructive. Then outside these, secondary lobes form. The secondary lobe forms where path length differences create a full cycle shift. If the individual source beamwidths are narrow enough, the secondary lobes will be small. If source beamwidths are large, the secondary lobes will be also.

Movement along the horizontal axis does not create a path length difference, except that caused by the source area, the very reason that the midwoofer becomes directional in the first place. But there is no path length difference change between acoustic centers. So summing is generally constructive out to fairly large angles, where the directivity of the piston sets in. There summing becomes complex, something like the situation with the verticals. So the edge of the pattern in the horizontal is usually a little bit lumpy through the crossover region as a result.

That's why I describe the combined output of the two sources in the overlap region as being "blended." It's also why I like to match their directivities as much as possible, by choosing crossover where the beamwidths of the two subsystems match. I have seen some describe pushing the crossover point so low directivity "matching" is effectively done down where both sources radiation patterns approach omnidirectional. I think this is a bad practice, both because of the summing/blending thing I just described and also because compression drivers are strained when running them too low.

Last edited:

I am not sure one can realistically make a broad brush generalization, one needs to add some qualifiers.

For example, if you listen outdoors and are just one listener then the directivity is essentially* irrelevant as nothing but the direct sound and ground bounce reaches your ears. If you want several people to experience the identical reproduction at the same time, then what you want is the same response vs position.

*The only way how the one loudspeakers radiates anechoic or outdoors that is audible in this case is the degree of homogeneity, if what reaches the R and L ears is substantially identical, there is very little audible clue as to the loudspeakers physical location in depth. If not, one can easily identify the depth location (with eyes closed) and in the latter case one using a pair in stereo will also hear a R&L source as well as the phantom image playing a mono signal, where the former the R&L sources gone / greatly suppressed leaving a stronger mono phantom. This is unrelated to musical enjoyment or pleasure unless you’re into that (I am).

The easiest way to get that simple radiation is with an acoustically small source which automatically has a wide and simple dispersion pattern. A small full range driver on a large flat baffle (eq’d flat) demonstrates this over some bandwidth.

Once one has moved into a room, things change a lot.

loudspeaker directivity is tied to acoustic size while in the market “small is better” with music enjoyment being subjective and many magazines generally a for hire marketing agents and not sources of real information, things are not very clear in hifi land.

BUT elsewhere, if one is concerned with preserving the information in the recording or one needs to understand words, then directivity is very important. Here, no amount of added room stuff brings you closer to the recording than none. It IS reflected sound that fills in the MTF’s which limit the resolution. If you’re not familiar with STIpa or MTF’s, here is the optical MTF analogue.

http://photo.net/learn/optics/mtf/blur2.gif

For information transfer like speech or here for inter-aural cross talk cancellation to work it’s best it was concluded “Loudspeaker directivity is the single most important loudspeaker property for 3D audio with crosstalk cancellation, since room reflections directly degrade the level of crosstalk cancellation.”

3D3A Lab at Princeton University

The same degradation is present with the original signal as well and it is also better preserved at the LP with directivity vs not.

Here is another odd thing in hifi, people obsess about “flatness” and other one meter measurements and they do matter, yet few listen at one meter and what you measure at the LP is certainly more like / is actually what you experience.

It really does seem like the concept in commercial sound that what you experience or measure at the LP is what matters most, that this would / does apply in hifi too and here is where directivity is your friend.

Alternately, among the things which degrade the MTF measurements which comprise the STIpa speech intelligibility prediction is reflected sound.

At work in commercial sound, I have proposed a figure of merit for CD sources too, it would be the difference between the energy in the stated pattern, vs the energy outside the stated pattern. This is something like DI or Q but now includes the intended pattern instead of only a 0 degree reference. This way one can say that say 90% of the total energy is where you intend while 10% is going elsewhere and potentially exciting the reverberant field that half goes where you want and half elsewhere etc.

If preserving the information arriving at the listener is important, then so is directivity if you’re in a room, if enjoyment is the only measure, then anything that works, well, works even 6X9’s on the back deck .

As Bill mentioned, the Synergy horn design is a way to avoid all the interactions from multiple sources. It is a way to drive a horn and radiate ‘as if” there was only one impossible broadband driver even though there may be a large number. One common thing to all of them is that you can walk up and even put your head into the horn and you never hear any more than one sound source floating in front of you.

While for commercial sound the products at work must have a full 3d radiation model (data taken by an independent lab, every 5 degrees over a full sphere in a reflection free area) the format doesn’t plot out the spectrogram style map popular in hifi.

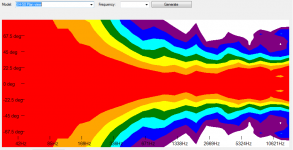

I did ask Sebastian our software guy to take the CLF data and plot a Horizontal map for an SH-50, one of our oldest Synergy horns (I use them at home, a 7 driver, 3 way horn system). Larger than a hifi speaker with pattern control to a lower frequency as a result.

Note this is a full bandwidth plot, 3dB per color, front 180 degrees, extracted from the CLF data, the left frequency boundary is 30Hz not 200Hz.

Wayne, I hope you weren’t too close to the tornadoes, my heart goes out to those who lost and were harmed.

Tom

For example, if you listen outdoors and are just one listener then the directivity is essentially* irrelevant as nothing but the direct sound and ground bounce reaches your ears. If you want several people to experience the identical reproduction at the same time, then what you want is the same response vs position.

*The only way how the one loudspeakers radiates anechoic or outdoors that is audible in this case is the degree of homogeneity, if what reaches the R and L ears is substantially identical, there is very little audible clue as to the loudspeakers physical location in depth. If not, one can easily identify the depth location (with eyes closed) and in the latter case one using a pair in stereo will also hear a R&L source as well as the phantom image playing a mono signal, where the former the R&L sources gone / greatly suppressed leaving a stronger mono phantom. This is unrelated to musical enjoyment or pleasure unless you’re into that (I am).

The easiest way to get that simple radiation is with an acoustically small source which automatically has a wide and simple dispersion pattern. A small full range driver on a large flat baffle (eq’d flat) demonstrates this over some bandwidth.

Once one has moved into a room, things change a lot.

loudspeaker directivity is tied to acoustic size while in the market “small is better” with music enjoyment being subjective and many magazines generally a for hire marketing agents and not sources of real information, things are not very clear in hifi land.

BUT elsewhere, if one is concerned with preserving the information in the recording or one needs to understand words, then directivity is very important. Here, no amount of added room stuff brings you closer to the recording than none. It IS reflected sound that fills in the MTF’s which limit the resolution. If you’re not familiar with STIpa or MTF’s, here is the optical MTF analogue.

http://photo.net/learn/optics/mtf/blur2.gif

For information transfer like speech or here for inter-aural cross talk cancellation to work it’s best it was concluded “Loudspeaker directivity is the single most important loudspeaker property for 3D audio with crosstalk cancellation, since room reflections directly degrade the level of crosstalk cancellation.”

3D3A Lab at Princeton University

The same degradation is present with the original signal as well and it is also better preserved at the LP with directivity vs not.

Here is another odd thing in hifi, people obsess about “flatness” and other one meter measurements and they do matter, yet few listen at one meter and what you measure at the LP is certainly more like / is actually what you experience.

It really does seem like the concept in commercial sound that what you experience or measure at the LP is what matters most, that this would / does apply in hifi too and here is where directivity is your friend.

Alternately, among the things which degrade the MTF measurements which comprise the STIpa speech intelligibility prediction is reflected sound.

At work in commercial sound, I have proposed a figure of merit for CD sources too, it would be the difference between the energy in the stated pattern, vs the energy outside the stated pattern. This is something like DI or Q but now includes the intended pattern instead of only a 0 degree reference. This way one can say that say 90% of the total energy is where you intend while 10% is going elsewhere and potentially exciting the reverberant field that half goes where you want and half elsewhere etc.

If preserving the information arriving at the listener is important, then so is directivity if you’re in a room, if enjoyment is the only measure, then anything that works, well, works even 6X9’s on the back deck .

As Bill mentioned, the Synergy horn design is a way to avoid all the interactions from multiple sources. It is a way to drive a horn and radiate ‘as if” there was only one impossible broadband driver even though there may be a large number. One common thing to all of them is that you can walk up and even put your head into the horn and you never hear any more than one sound source floating in front of you.

While for commercial sound the products at work must have a full 3d radiation model (data taken by an independent lab, every 5 degrees over a full sphere in a reflection free area) the format doesn’t plot out the spectrogram style map popular in hifi.

I did ask Sebastian our software guy to take the CLF data and plot a Horizontal map for an SH-50, one of our oldest Synergy horns (I use them at home, a 7 driver, 3 way horn system). Larger than a hifi speaker with pattern control to a lower frequency as a result.

Note this is a full bandwidth plot, 3dB per color, front 180 degrees, extracted from the CLF data, the left frequency boundary is 30Hz not 200Hz.

Wayne, I hope you weren’t too close to the tornadoes, my heart goes out to those who lost and were harmed.

Tom

Attachments

I demonstrate this kind of peaking during the talk by showing different crossovers, some that are more vulnerable to impedance peaks and create an audible response peak. We play music through these crossovers and waveguides, and I flip a switch to compare one crossover that can damp the modes with another that cannot. The attendees of the seminar all hear it, as they see it on the transfer function on the overhead projector.

Not saying that there is no audible difference but giving people a visual feedback of an audible change they are going to hear will make virtually everybody hear a change even if it's not there.

Probably everybody knows this article: Audio Musings by Sean Olive: The Dishonesty of Sighted Listening Tests

...and this one: McGurk effect - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Markus, the peaking I'm talking about is a pretty large peak. Put a 33 ohm resistor in series with your waveguide, for example. Don't put in any shunt resistance, so the impedance peaks near cutoff are transformed into the response curve. There's no way you won't hear that.

Subtle stuff needs a double blind, I would agree. But big stuff is obvious. A 5dB peak that's a half octave wide is obvious.

Tom, thanks for the thoughts. We were in the path, but in Tulsa, we didn't get the brunt of it.

Kevin, I matched the H290C throat entrance to the DE250 compression driver exactly. The catenary curve in the waveguide starts at that angle and progresses from there. I think that's the way the SEOS family of waveguides are too, for what it's worth.

Subtle stuff needs a double blind, I would agree. But big stuff is obvious. A 5dB peak that's a half octave wide is obvious.

Tom, thanks for the thoughts. We were in the path, but in Tulsa, we didn't get the brunt of it.

Kevin, I matched the H290C throat entrance to the DE250 compression driver exactly. The catenary curve in the waveguide starts at that angle and progresses from there. I think that's the way the SEOS family of waveguides are too, for what it's worth.

It's the same thingPeople simply don't use precise wording.

What kind of directivity is that - constant or uniform?

I assumed that Wayne meant uniform power response in regards to directivity....at least that's how I read it.

- Status

- This old topic is closed. If you want to reopen this topic, contact a moderator using the "Report Post" button.

- Home

- Loudspeakers

- Multi-Way

- Uniform Directivity - How important is it?