This article appeared in the New York Times on November 9th, it isn't archived so can't be cut and paste -- I have made an attempt to OCR it --

"HARRY WEISFELD is a celebrity among audiophiles — sound snobs, if you prefer. But to grasp his aural magnitude in full, to wrap yourself around just how big a star he is in this geeky, if growing, subculture, you need to sit down with his wife, Sheila.

Mr. Weisfeld, 55, is not unapproachable, but he is modest, as well as busy. An inveterate tinkerer, he is most at ease tweaking equipment at home in his basement here in Holmdel in Middlesex County or taking care of business at his company, VPI Industries, a few miles away in Cliffwood. His wife, 54, helps fill in the gaps, especially when he is confronted by the curious, which happens, she says, “all the time” at record shows and other industry appearances.

Attention like that goes with the engineering-luminary territory, particularly if, as in Mr. Weisfeld’s case, refining gadgets for obsessive music fans is involved. To make a turntable that draws rave reviews requires concentration; to hear a sound thinning from a long-playing record as the needle is raised one-thousandth of an inch requires an understanding of the many shades of quiet.

Mr. Weisfeld has designed equipment for the Library of Congress, record companies like Polygram and musicians like Paul Schaeffer, the band leader and David Letterman sidekick. Mr. Weisfeld’s first milestone, however, came years ago, in 1,8, when he opened VPI Industries after shopping around his first record-cleaning machine, which he had built using materials salvaged from his job as an apprentice sheetmetal worker.

The Weisfelds negotiated with the Singer Group in Westbury, N.Y., to sell the machine. “They were fighting over it,” his wife recalled of employees at Singer who all wanted to take the machine home and clean their records with it that night.

Next came a favorable magazine article about the machine. “The guy who reviewed it told me, ‘You’re going to be selling a lot of them, so you better start a business,’” Mr. Weisfeld said.

And so, VPI Industries was born. (It is unclear what VPI stands for, and both the Weisfelds clam up mysteriously when asked to explain.) The company originated in Queens, where the Weisfelds lived until a lack of space and a quest for better public schools for their two young sons

uprooted them to New Jersey in 1987.

The VPI office in Cliffwood is hardly bigger than a cubicle. Outfitted with a single desk, a chair and a constantly ringing tele

phone, it sits in the center of a single-story, concrete-slab office complex directly off the Garden State Parkway. Five steps in,

a turn to the left leads to the nexus of activity , a workshop-factory strewn with drills, stray parts and six assemblymen. An

upright row of turntable arms awaiting inspection resembles a line of Rockettes frozen in mid-kick.

Mrs. Weisfeld handles the company’s sales. For years its sole offering was that first cleaning machine, the HW-16, a

not-unusual name in an arsenal of products that seem extracted from a “Star Wars” screenplay. Upgrades like the VPI

HW-16.5 and the HW-17 Bi-Directional don’t exactly roll off the tongue either, but because these machines expertly slough

away groove-deep dirt, which can spell the ruination of irreplaceable vinyl, they account for 50 percent of VPI’s current

business and are back-ordered each month to places like England, Hong Kong, Israel, Italy, Russia, Switzerland and Thailand,

Mrs. Weisfeld said.

But if the cleaners keep record collectors returning to VPI, it’s the turntables, which Mr. Weisfeld started making in 1981,

that have cultivated the company’s considerable swagger. Even the mass-market format switchover from vinyl to tape

cassettes, and to compact discs in the 1980’s, did not dent VPI’s sales.

TO BE CONTINUED (Too long for one post)

"HARRY WEISFELD is a celebrity among audiophiles — sound snobs, if you prefer. But to grasp his aural magnitude in full, to wrap yourself around just how big a star he is in this geeky, if growing, subculture, you need to sit down with his wife, Sheila.

Mr. Weisfeld, 55, is not unapproachable, but he is modest, as well as busy. An inveterate tinkerer, he is most at ease tweaking equipment at home in his basement here in Holmdel in Middlesex County or taking care of business at his company, VPI Industries, a few miles away in Cliffwood. His wife, 54, helps fill in the gaps, especially when he is confronted by the curious, which happens, she says, “all the time” at record shows and other industry appearances.

Attention like that goes with the engineering-luminary territory, particularly if, as in Mr. Weisfeld’s case, refining gadgets for obsessive music fans is involved. To make a turntable that draws rave reviews requires concentration; to hear a sound thinning from a long-playing record as the needle is raised one-thousandth of an inch requires an understanding of the many shades of quiet.

Mr. Weisfeld has designed equipment for the Library of Congress, record companies like Polygram and musicians like Paul Schaeffer, the band leader and David Letterman sidekick. Mr. Weisfeld’s first milestone, however, came years ago, in 1,8, when he opened VPI Industries after shopping around his first record-cleaning machine, which he had built using materials salvaged from his job as an apprentice sheetmetal worker.

The Weisfelds negotiated with the Singer Group in Westbury, N.Y., to sell the machine. “They were fighting over it,” his wife recalled of employees at Singer who all wanted to take the machine home and clean their records with it that night.

Next came a favorable magazine article about the machine. “The guy who reviewed it told me, ‘You’re going to be selling a lot of them, so you better start a business,’” Mr. Weisfeld said.

And so, VPI Industries was born. (It is unclear what VPI stands for, and both the Weisfelds clam up mysteriously when asked to explain.) The company originated in Queens, where the Weisfelds lived until a lack of space and a quest for better public schools for their two young sons

uprooted them to New Jersey in 1987.

The VPI office in Cliffwood is hardly bigger than a cubicle. Outfitted with a single desk, a chair and a constantly ringing tele

phone, it sits in the center of a single-story, concrete-slab office complex directly off the Garden State Parkway. Five steps in,

a turn to the left leads to the nexus of activity , a workshop-factory strewn with drills, stray parts and six assemblymen. An

upright row of turntable arms awaiting inspection resembles a line of Rockettes frozen in mid-kick.

Mrs. Weisfeld handles the company’s sales. For years its sole offering was that first cleaning machine, the HW-16, a

not-unusual name in an arsenal of products that seem extracted from a “Star Wars” screenplay. Upgrades like the VPI

HW-16.5 and the HW-17 Bi-Directional don’t exactly roll off the tongue either, but because these machines expertly slough

away groove-deep dirt, which can spell the ruination of irreplaceable vinyl, they account for 50 percent of VPI’s current

business and are back-ordered each month to places like England, Hong Kong, Israel, Italy, Russia, Switzerland and Thailand,

Mrs. Weisfeld said.

But if the cleaners keep record collectors returning to VPI, it’s the turntables, which Mr. Weisfeld started making in 1981,

that have cultivated the company’s considerable swagger. Even the mass-market format switchover from vinyl to tape

cassettes, and to compact discs in the 1980’s, did not dent VPI’s sales.

TO BE CONTINUED (Too long for one post)

Attachments

Part deux

“It’s funny,” Mr. Weisfeld said. “I was at a used-record show a couple of weeks ago” ,the Raritan Records show, in

September, offered Mrs. Weisfeld , “and I was amazed by the people there who were less than 30. I asked a couple of guys,

“Why are you here?’ They said it’s because if they have $50, they can buy 50 records, not just three CD’s. People used

to ask me in 1985, when the CD was getting big, “What are you going to do in five years?’ But vinyl is bigger than ever

now; you can buy tons of new vinyl.”

VPI, which is a private company and also has a small factory in Pennsylvania, says its vinyl sales increased 40 percent from

1999 to 2002.

In addition, Sundazed Records in Coxsackie, N.Y., recently arrived on the LP scene as a reproducer of fuzz-damaged clas

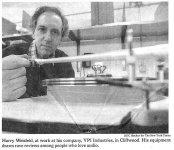

;Harry Weisfeld, at work at his company, VPI Industries, in Cliffwood. His equipment draws rave reviews among people

who love audio.

sics by vintage acts like the Young Rascals.

But depending on a collector’s aural standards, even the new vinyl can sound subpar.

The under-30 guys bearing $50 who caught Mr. Weisfeld’s attention at the record show (virtually everybody at a

used-record show is a guy, explained Mrs. Weisfeld; “You get a token woman here or there, but not many”) probably aren

‘t the same ones wait-listed months for VPI’s 160-pound, $10,000 TNT HRX turntable, which is praised by Stereophile

and HiFi+ magazines as among the finest machines ever made. Those customers tend to be “six doctors with huge amounts

of disposable income,” Mr. Weisfeld said, or jazz aficionados desperate to re-create Miles Davis’s recording session for a

masterpiece album like “Kind of Blue.” But in some ways, the younger, less affluent customers are the kind Mr. Weisfeld

relates to best.

“After all,” his wife said, “that’s how he started out. He was hanging around these audio stores hoping to buy all this

great equipment 30 years ago, when we were first married and had to pay the mortgage. He was a sheetmetal worker. He had

to build his own.”

Mrs. Weisfeld, with her straight, center-parted hair, large glasses and oh-brother demeanor, resembles a red-headed version of

the comic strip heroine “Cathy.”

Mr. Weisfeld, who works in jeans and untucked shirts and is just tall and lean enough to be considered lanky, doesn’t have

the

frown lines of a 55-year-old despite his graying hair, and he speaks slowly and clearly in an accent that gives away his

Brooklyn upbringing.

The recently rolled-out Scout turntable, which is priced at $1,600 and weighs in at a relatively feathery 37 pounds, is among

his proudest achievements.

“It’s easy to make a $10,000 machine sound great,” he said, “but it’s a lot harder for something that costs $1,600 to

sound great,” owing to the necessity of a smaller base and platter.

“I can hear a record on the Scout, and it sounds like reel-to-reel,” he added. “It sounds natural.” Certain records, like his

newly acquired recording of Vaughn Monroe singing “Ghost Riders in the Sky” or several of the Frank Sinatra LP’s he

favors, “give me goose bumps,” he said. And that does not happen all the time to somebody in possession of an ear like his.

“If you listen to the human voice,” Mr. Weisfeld pointed out casually, seemingly aware of the ease with which audiospeak

can be confused with pretentiousness, “there’s no halo. You don’t hear a voice sparkle. With bass, there’s a white halo

all around it. Systems will do that if they’re not accurate.”

The typical top-40 listener might not know sparkles from halos. But many others do, and that is largely why LP’s have

retained their allure. Jazz fans, the lustiest, technogeekiest VPI customers, lead the pack.

“With jazz, people want to hear it the way

the guy who did the original mastering heard it; people who knew how Count Basie, Miles Davis and Duk& Ellington wanted

to sound,” Mr. Weisfeld said. “These are musicians who were around during World War II, and they brought that fire to

their music. Nobody else has gone through what they went through, and you can’t reproduce it.

“Guys in the mid-70’s started adding more bass, more treble, saying, “Let’s zoom it up.’ But people want to hear it the

way it actually sounded. They want to feel they’re in the same room.”

Surprisingly, Mr. Weisfeld likes the compact disc. “But it doesn’t have enough resolution,” he said. “When it was

designed they didn’t have the computing powers they have now.” The latest format, Sony’s SuperAudio CD, “is almost

up to the level of vinyl but not quite there,” he said.

For her part, Mrs. Weisfeld could do without the aural splitting of hairs that constantly surrounds her, although experience has

enabled her to suss out minute sounds alongside the fussiest fellow Audiophile Society member. Her position is that “being

an audiophile is a selfish hobby.”

“I can’t really appreciate it,” she said. “When I want to listen to something, I want to sit down and listen to it. But with

Harry, he has to jump up all the time and adjust things.” Left to her own listening devices, she added, “I’d never touch his

turntables. If I scratch a record, forget it.”

Still, Mrs. Weisfeld remains as dedicated a supporter of her husband’s ingenuity as anybody , “I can break anything, and

he can fix anything, so it works out” , and it was chiefly her patience and support that lifted the couple and their business out

of a devastating personal crisis several years ago.

In 1995, the Weisfelds’ elder son, Jonathan, a 17-year-old aspiring musician, was killed in a car accident with two other

HoImdel High students. While Mrs. Weisfeld im- I mersed herself in helping their younger son, Mat, cope and in promoting

safety-awareness programs in the community, “Harry ~ isolated himself,” she said. VPI closed for a month, and Mr.

Weisfeld spent about two ~. years in the basement making tonearms ,the part of a turntable that holds the needle cartridge.

The result, the JMW Memorial Tonearm, whose sales benefit a memorial fund for Jonathan, was born of grief, but reviewers

point out its flair for enabling music to spring to life. The secret, Mr. Weisfeld says, is in its pivot , an absence of bearings on

both sides lets the tonearm float freely, without friction, which can “fog the sound” of an LP.

A five-star evaluation that appeared in the magazine The Absolute Sound said: “If this arm had been a disappointment, I

would have passed on its review. But Harry Weisfeld, for whom the arm’s creation became an act of love, has fashioned a

tribute to the spirit of music. With this arm, he has done by far the best work of his career. There is life; the music dances.”

“It’s funny,” Mr. Weisfeld said. “I was at a used-record show a couple of weeks ago” ,the Raritan Records show, in

September, offered Mrs. Weisfeld , “and I was amazed by the people there who were less than 30. I asked a couple of guys,

“Why are you here?’ They said it’s because if they have $50, they can buy 50 records, not just three CD’s. People used

to ask me in 1985, when the CD was getting big, “What are you going to do in five years?’ But vinyl is bigger than ever

now; you can buy tons of new vinyl.”

VPI, which is a private company and also has a small factory in Pennsylvania, says its vinyl sales increased 40 percent from

1999 to 2002.

In addition, Sundazed Records in Coxsackie, N.Y., recently arrived on the LP scene as a reproducer of fuzz-damaged clas

;Harry Weisfeld, at work at his company, VPI Industries, in Cliffwood. His equipment draws rave reviews among people

who love audio.

sics by vintage acts like the Young Rascals.

But depending on a collector’s aural standards, even the new vinyl can sound subpar.

The under-30 guys bearing $50 who caught Mr. Weisfeld’s attention at the record show (virtually everybody at a

used-record show is a guy, explained Mrs. Weisfeld; “You get a token woman here or there, but not many”) probably aren

‘t the same ones wait-listed months for VPI’s 160-pound, $10,000 TNT HRX turntable, which is praised by Stereophile

and HiFi+ magazines as among the finest machines ever made. Those customers tend to be “six doctors with huge amounts

of disposable income,” Mr. Weisfeld said, or jazz aficionados desperate to re-create Miles Davis’s recording session for a

masterpiece album like “Kind of Blue.” But in some ways, the younger, less affluent customers are the kind Mr. Weisfeld

relates to best.

“After all,” his wife said, “that’s how he started out. He was hanging around these audio stores hoping to buy all this

great equipment 30 years ago, when we were first married and had to pay the mortgage. He was a sheetmetal worker. He had

to build his own.”

Mrs. Weisfeld, with her straight, center-parted hair, large glasses and oh-brother demeanor, resembles a red-headed version of

the comic strip heroine “Cathy.”

Mr. Weisfeld, who works in jeans and untucked shirts and is just tall and lean enough to be considered lanky, doesn’t have

the

frown lines of a 55-year-old despite his graying hair, and he speaks slowly and clearly in an accent that gives away his

Brooklyn upbringing.

The recently rolled-out Scout turntable, which is priced at $1,600 and weighs in at a relatively feathery 37 pounds, is among

his proudest achievements.

“It’s easy to make a $10,000 machine sound great,” he said, “but it’s a lot harder for something that costs $1,600 to

sound great,” owing to the necessity of a smaller base and platter.

“I can hear a record on the Scout, and it sounds like reel-to-reel,” he added. “It sounds natural.” Certain records, like his

newly acquired recording of Vaughn Monroe singing “Ghost Riders in the Sky” or several of the Frank Sinatra LP’s he

favors, “give me goose bumps,” he said. And that does not happen all the time to somebody in possession of an ear like his.

“If you listen to the human voice,” Mr. Weisfeld pointed out casually, seemingly aware of the ease with which audiospeak

can be confused with pretentiousness, “there’s no halo. You don’t hear a voice sparkle. With bass, there’s a white halo

all around it. Systems will do that if they’re not accurate.”

The typical top-40 listener might not know sparkles from halos. But many others do, and that is largely why LP’s have

retained their allure. Jazz fans, the lustiest, technogeekiest VPI customers, lead the pack.

“With jazz, people want to hear it the way

the guy who did the original mastering heard it; people who knew how Count Basie, Miles Davis and Duk& Ellington wanted

to sound,” Mr. Weisfeld said. “These are musicians who were around during World War II, and they brought that fire to

their music. Nobody else has gone through what they went through, and you can’t reproduce it.

“Guys in the mid-70’s started adding more bass, more treble, saying, “Let’s zoom it up.’ But people want to hear it the

way it actually sounded. They want to feel they’re in the same room.”

Surprisingly, Mr. Weisfeld likes the compact disc. “But it doesn’t have enough resolution,” he said. “When it was

designed they didn’t have the computing powers they have now.” The latest format, Sony’s SuperAudio CD, “is almost

up to the level of vinyl but not quite there,” he said.

For her part, Mrs. Weisfeld could do without the aural splitting of hairs that constantly surrounds her, although experience has

enabled her to suss out minute sounds alongside the fussiest fellow Audiophile Society member. Her position is that “being

an audiophile is a selfish hobby.”

“I can’t really appreciate it,” she said. “When I want to listen to something, I want to sit down and listen to it. But with

Harry, he has to jump up all the time and adjust things.” Left to her own listening devices, she added, “I’d never touch his

turntables. If I scratch a record, forget it.”

Still, Mrs. Weisfeld remains as dedicated a supporter of her husband’s ingenuity as anybody , “I can break anything, and

he can fix anything, so it works out” , and it was chiefly her patience and support that lifted the couple and their business out

of a devastating personal crisis several years ago.

In 1995, the Weisfelds’ elder son, Jonathan, a 17-year-old aspiring musician, was killed in a car accident with two other

HoImdel High students. While Mrs. Weisfeld im- I mersed herself in helping their younger son, Mat, cope and in promoting

safety-awareness programs in the community, “Harry ~ isolated himself,” she said. VPI closed for a month, and Mr.

Weisfeld spent about two ~. years in the basement making tonearms ,the part of a turntable that holds the needle cartridge.

The result, the JMW Memorial Tonearm, whose sales benefit a memorial fund for Jonathan, was born of grief, but reviewers

point out its flair for enabling music to spring to life. The secret, Mr. Weisfeld says, is in its pivot , an absence of bearings on

both sides lets the tonearm float freely, without friction, which can “fog the sound” of an LP.

A five-star evaluation that appeared in the magazine The Absolute Sound said: “If this arm had been a disappointment, I

would have passed on its review. But Harry Weisfeld, for whom the arm’s creation became an act of love, has fashioned a

tribute to the spirit of music. With this arm, he has done by far the best work of his career. There is life; the music dances.”

Hi,

Very touching story and courageous of Harry Weisfeld, a man after my own heart.

Unipivots are the best if you can design them properly.

Cheers and thanks for sharing the story,

Very touching story and courageous of Harry Weisfeld, a man after my own heart.

With this arm, he has done by far the best work of his career. There is life; the music dances.”

Unipivots are the best if you can design them properly.

Cheers and thanks for sharing the story,

- Status

- This old topic is closed. If you want to reopen this topic, contact a moderator using the "Report Post" button.